New series exploring ILM’s 50-year legacy kicks off with new interviews featuring original Star Wars animator Chris Cassidy and current ILM animation supervisors Rob Coleman and Hal Hickel.

By Jamie Benning

“ILM Evolutions” is an ILM.com exclusive series exploring a range of visual effects disciplines and highlights from Industrial Light & Magic’s first 50 years of innovative storytelling.

Animation has been woven into the DNA of Industrial Light & Magic’s story since its earliest days. From utilizing legacy techniques in Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) to the groundbreaking blend of live-action and animation in Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), ILM has continually redefined the possibilities of visual storytelling.

In this two-part article, we explore ILM’s journey from early work with rotoscoping, stop-motion, and go-motion to the development of sophisticated digital character animation in Jurassic Park (1993), the Star Wars prequel trilogy, and beyond. Part one focuses on the key innovations that culminated in Rango (2011), ILM’s first fully animated feature film. Part two examines how the studio expanded on these foundations in Transformers One and Ultraman: Rising (both 2024), solidifying its role as a leader not only in visual effects but also in feature animation.

Early Innovations and Handcrafted Beginnings

In 1975, as Star Wars, later retitled Star Wars: A New Hope, entered production, Industrial Light & Magic was a fledgling outfit assembled to help realize George Lucas’s ambitious vision. Animation quickly proved essential to the storytelling – Lucas’s needs were varied, including spaceship models firing laser bolts, glowing lightsaber blades, a holographic chess game, and stylized targeting displays.

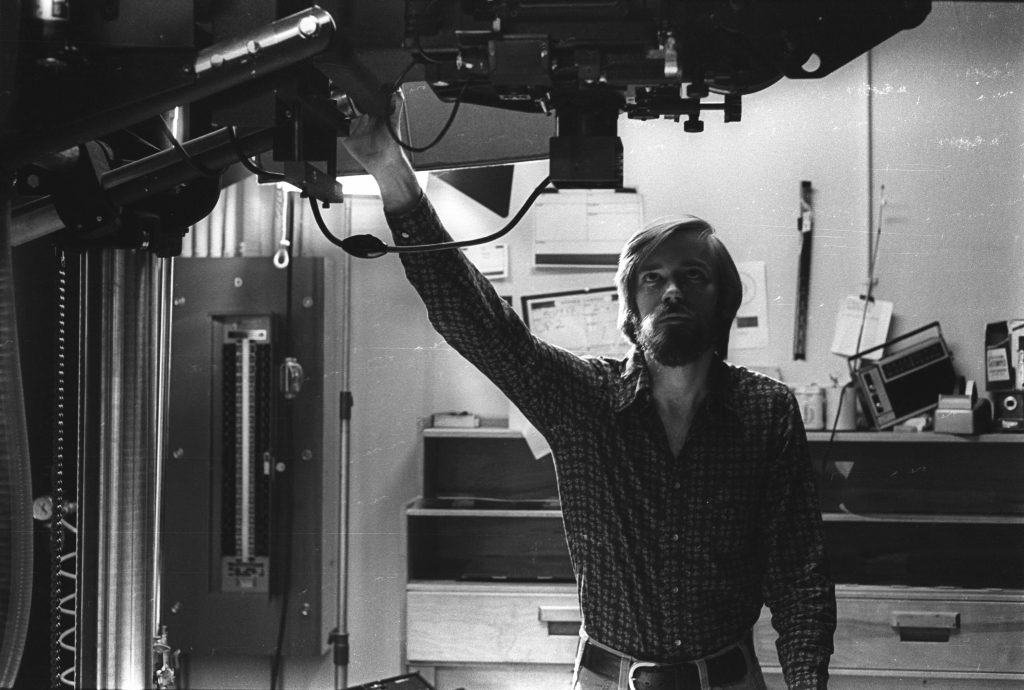

To create the signature blaster bolts, California Institute of the Arts graduate Adam Beckett was hired in July 1975 to lead a small team in creating the animation and rotoscoping – including a young Peter Kuran. “I was initially shooting wedges and different colors for the laser beams and stuff like that. I was learning to use the equipment. We all were,” Kuran told The Filmumentaries Podcast.

“I actually did the first perspective beams,” said Kuran. “What was being tested was just kind of like back and forth – no perspective on it. I had suggested that we try that, and I actually got a very chilly response. So I decided to stay late one night and do a test and took it to the lab myself. It ran as a daily the next day, and [visual effects supervisor] John Dykstra liked it, so I wound up being the chief of that, at least for the time being.”

The iconic lightsaber effects were outsourced to Van Der Veer Photo Effects for the first film but later brought in-house at ILM. The process began by generating mattes from the live-action prop blades. Early experiments with retroreflective material and spinning poles proved too complex and were eventually streamlined. The mattes were rephotographed and colored frame by frame, with hues used to help audiences distinguish between each character’s weapon – blue for Obi-Wan Kenobi, red for Darth Vader – setting the look for the Star Wars saga for decades to come.

“At first, ILM didn’t have the resources to do all the opticals themselves,” animator Chris Casady tells ILM.com. “They sent shots out to Van Der Veer, Cinema Research, and Modern Film Effects. Those places were the old guard – they’d done work on Logan’s Run (1976), Soylent Green (1973), that kind of thing.

“But the goal was always to bring everything in-house,” Casady adds. “And once ILM got the optical department up and running in Van Nuys, the quality jumped. We had more control, and it just looked better.”

Beckett, as described by Casady, “was without a doubt a genius. Adam was extremely brilliant. He wanted to be able to put some of his psychedelic style into Star Wars. He thought it was almost an obligation to one-up 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968]. But Lucas wanted something more realistic.”

Casady noted Beckett’s work on the Death Star superlaser charging sequence, explaining that “Adam did a tremendous amount of work putting together that Death Star laser tunnel shot – all those rings and green things flashing down the middle. It’s built up of multiple passes, multiple exposures, multiple pieces of artwork.” The platform on which the live-action actors were standing was completely hand-drawn by Peter Kuran.

Casady added that “Adam’s signature work is the electrocution of R2-D2,” an entirely hand-drawn effect requiring precision to make the electricity feel convincing on screen.

“I really was brought in at a grunt level to make garbage mattes on the animation stand at night to free up the VistaVision cameras in the daytime,” Casady explained. “Every time they filmed the spaceship on stage … everything outside the blue is considered garbage; it’s got to be masked out. So, my job was to make this matte and block out the garbage.

“On film, my mattes fell below the threshold of black, so it became black,” Casady continues. “Famously, when the film was first released on VHS … my mattes were visible in the negative. … The audience saw my garbage mattes as irregular shapes that jumped every six or eight frames. So that’s the only time people got to see my work on the film!”The animation team also solved another subtle but crucial challenge: making the miniature spaceship models feel more plausible in their scenes.

“There was a shot of a TIE Fighter flying past the camera, and they were concerned it looked too flat,” said Casady. “So they asked if we could paint in some reflections – highlights that would suggest the ship was catching light from the environment. It wasn’t baked into the model photography, so we had to add those glints manually, frame by frame, right onto the animation cels. Just little touches of light to make it feel like the ship belonged in that space.”

Kuran told The Filmumentaries Podcast, “I just thought that that was something that was needed.”

By the time Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) came around, ILM was called on to create yet another iconic animated visual effect: Emperor Palpatine’s Force lightning. Composed of hand-drawn electrical arcs, the effect required animator Terry Windell to conjure a sense of living, dangerous energy – a visual shorthand for the raw power of the dark side. During his career, Windell brought his animation skills to Poltergeist (1982) and Ghostbusters (1984), among many others.

Though Peter Kuran had since left ILM, his company, Visual Concept Engineering, took on the painstaking task of rotoscoping each frame of the lightsaber combat between Luke and Vader. In total, 102 lightsaber shots were completed for the final film in the trilogy.

While rotoscoping and hand-drawn animation effects remained essential throughout the early 1980s, ILM was already looking ahead, seeking ways to evolve another time-honored technique: stop-motion animation.

The Rise of Go-Motion

Before work began on Return of the Jedi, “Go-Motion” – a breakthrough in dimensional animation pioneered by ILM’s Dennis Muren, Phil Tippett, Stuart Ziff, and Tom St. Amand – offered a major refinement to traditional stop-motion by introducing motion blur, an effect crucial to achieving realistic movement. Unlike standard stop-motion, where models remain static during each frame’s exposure, go-motion employs stepper motors driven by a motion-control system. These motors subtly shift the puppet during the open-shutter phase, simulating the kind of motion blur found in live-action 24fps cinematography.

“The significance is that we got it working,” Ziff told Cinefex, downplaying the complexity of a system that required months of development before the first usable shot could be captured.

First explored during production on Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980) and fully realized on Dragonslayer (1981), the process eliminated the telltale staccato of conventional stop-motion.

Ziff’s engineering expertise led to the development of a modular rig dubbed the “Dragon Mover,” which connected to the model’s limbs via rods and enabled precise, repeatable motion sequences. Tippett, St. Amand, and Ken Ralston meticulously animated both walking and flying versions of the puppet, blending mechanical precision with handcrafted nuance.

“We started off with some of the more complicated shots,” Tippett told Cinefex, recalling the weeks spent programming movement cycles before finally achieving a fluid, natural gait. This meant that the process became easier over time, a testament to the artists’ dual roles as problem solvers. The result was a new level of fluidity and realism, particularly evident in the scenes featuring the film’s dragon, Vermithrax Pejorative.

Blending Animation with Live-Action: A New Frontier

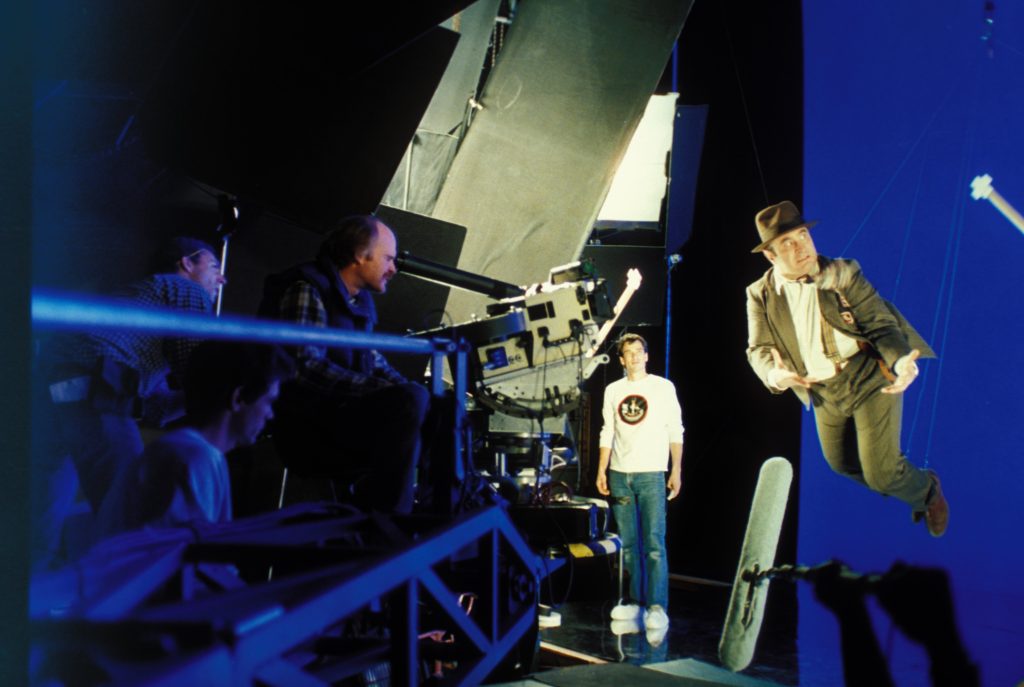

ILM’s reputation for innovation took a significant leap forward with Who Framed Roger Rabbit. Directed by Robert Zemeckis, the film demanded the seamless integration of hand-drawn, cel-animated characters with live-action performances and practical on-set effects. ILM’s task was to anchor the animated characters convincingly in the real world.

Visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston oversaw the technical and creative challenges of making cartoon characters interact believably with real environments. “The animation had to exist in a real world, with real lighting, perspective, and interaction. That had never been done before at this level,” Ralston told Cinefex.

“It was great for me because I am a huge fan of those early cartoons by the great Warner Brothers directors, Tex Avery and Chuck Jones. And when that showed up with the intent that Bob [Zemeckis] wanted for it, man, that was a match made in heaven. And it was brutal, but it was great at the same time. It keeps you going. And when you see results on something that’s finally coming together, it’s a blast,” Ralston explained to The Filmumentaries Podcast.

Marking a turning point in hybrid filmmaking, they also decided to discard the traditional locked-off camera in favor of dynamic movement. To support this, ILM developed new methods to track live-action camera motion and translate it into data that animators could use to maintain consistent character positioning and perspective. “The opening camera crane shot proved to be historic. … No one had ever done a crane drop with a live-action camera and planted an animated character firmly on the ground,” Zemeckis recalled to Cinefex.

ILM and the special effects team constructed practical rigs to simulate interactions between live-action props and invisible cartoon characters. In one sequence, when Roger Rabbit turns a water faucet, a hidden mechanism releases a perfectly timed spray – a practical effect used to sell the interaction.

To match the shifting light within live-action environments, ILM tracked moving shadows and highlights, ensuring the animated characters were illuminated just like the actors. “If a light in the scene was swinging, … then the Toon characters would have to be lit in exactly the same way,” said Ralston. Animators relied on detailed lighting references to maintain visual consistency frame by frame.

Performance presented its own challenges. Bob Hoskins, cast as Eddie Valiant, was required to act opposite characters that weren’t physically present. “What I had to do was spend hours developing a technique to actually see, hallucinate, virtually to conjure these characters up,” he told Cinefex. To assist, Charles Fleischer, the voice of Roger Rabbit, wore a full Roger costume off-camera and delivered his lines live. “Although he was on the other side of the camera, I was able to talk to him as if he were right next to me. We could even ad-lib together,” Hoskins said.

After principal photography wrapped, ILM tackled the complex process of optical compositing while Richard Williams’s animation team in London produced the character animation. ILM integrated those elements into the live-action footage. “Every frame had to go through multiple passes to create tone mattes, shadow mattes, and interactive lighting effects. It wasn’t just a matter of drawing the character,” explained optical supervisor Edward Jones. “Every single frame had to be drawn, rechecked, and composited with multiple elements to make sure the animation fit seamlessly into the live-action,” Zemeckis recalled.

The result was a groundbreaking fusion of animation and visual effects that redefined the possibilities in cinematic storytelling. It was a winning combination of traditional techniques and innovation that was widely praised. The film won Best Visual Effects and a Special Achievement Award at the 1989 Academy Awards. Many saw the film as the zenith of the photochemical era, even to the extent that it was perceived as too complex to repeat.

In fact, it wasn’t until a decade later that ILM revisited this hybrid format with The Adventures of Rocky and Bullwinkle (2000), applying many of the same techniques with enhanced digital compositing tools to a new generation of animated characters.

When Dinosaurs Ruled the Visual Effects World

While go-motion had proven a valuable innovation throughout the 1980s, it was the advent of computer graphics (CG) character animation that truly revolutionized ILM’s approach in the 1990s. In the last year of the decade, ILM laid the groundwork on James Cameron’s The Abyss (1989), animating the fully CG pseudopod – a water-based, tentacle-like entity. For Cameron’s next film, Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), ILM once again raised the bar with the liquid metal T-1000.

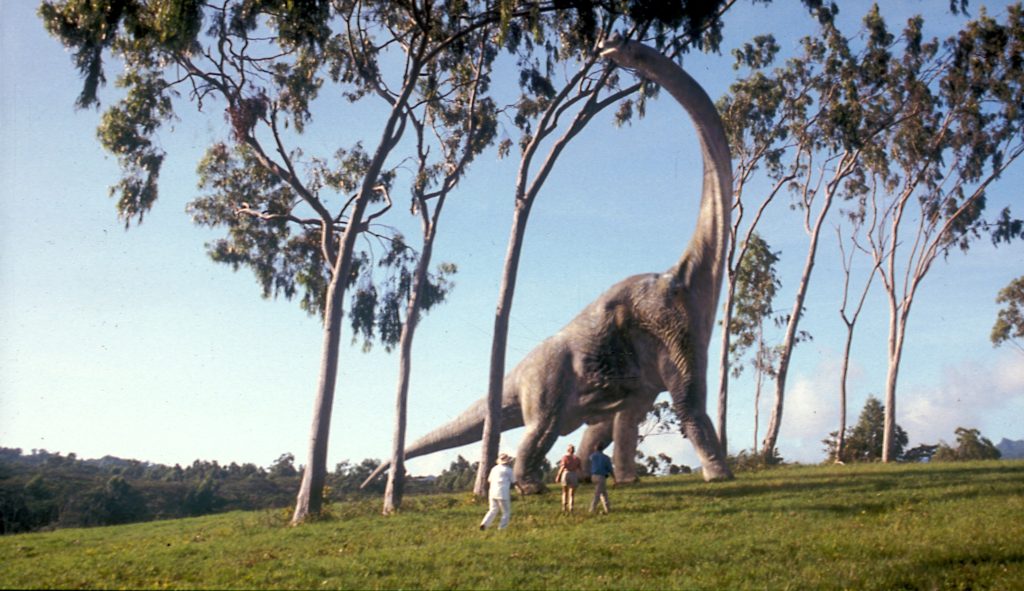

It was the digital dinosaurs in Jurassic Park that marked a true turning point – not just in terms of spectacle – but as a clear signal that traditional methods like stop-motion and go-motion were being eclipsed by a new era of photorealistic CG. ILM animator Steve Williams, who had previously worked with Mark Dippé on The Abyss and Terminator 2, pushed the idea of fully computer-rendered dinosaurs further. The results were astonishing. Steven Spielberg’s action-horror hybrid delivered creatures that felt real. Animals that moved and breathed with skin that stretched and muscles that flexed.

As a veteran stop-motion animator, Phil Tippett famously quipped at the time: “I’ve just become extinct.” The line – part joke, part reality – captured the profound shift unfolding across visual effects departments. Tippett’s line was given to the film’s Dr. Malcom, played by Jeff Goldblum.

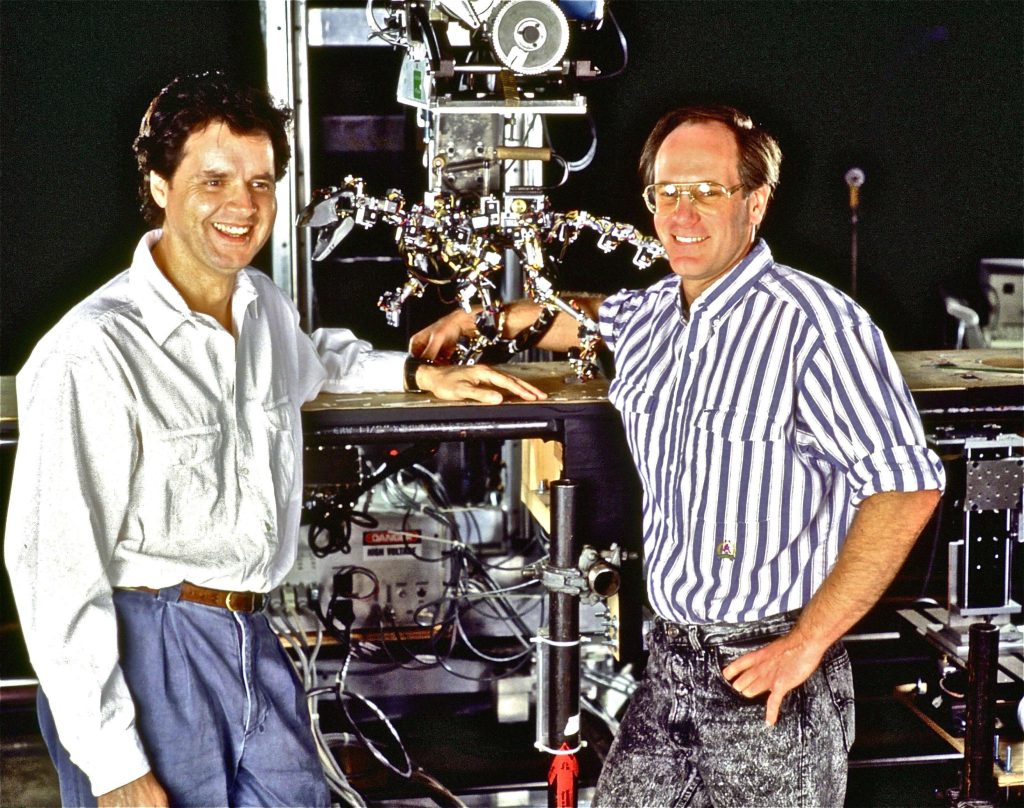

By the time Jurassic Park hit screens, the industry had begun pivoting decisively toward digital techniques, a shift witnessed firsthand by animator Rob Coleman.

“There were only 6 animators at ILM for Jurassic Park,” he tells ILM.com. “It was the film that inspired me to cut my reel and send it in. … And I came in as ILM’s animator number 9 in October of ‘93 (4 months after the film’s release) when it was still very early days for computer graphics.”

To bridge the gap between stop-motion and computer animation, the team developed a hybrid technique known as the Dinosaur Input Device or D.I.D. This setup used a dinosaur armature fitted with sensors and encoders, allowing animators to physically manipulate the model while their movements were captured and translated into digital data. The goal was to combine the skill and experience of the traditional animators and strengths of the computer artists and technicians. While the results weren’t always ideal – much of the animation still had to be keyframed in the computer – it marked a pivotal step. The future of filmmaking was taking shape, frame by frame.

The Challenge of Digital Characters: The Star Wars Prequels

Following ILM’s work in the 1990s on films like The Flintstones (1994), Casper (1995), Forrest Gump (1994), and Jumanji (1995), George Lucas was getting ready to revisit the galaxy far, far away. This time, with a vision that demanded unprecedented integration of digital characters and live-action performances. The Star Wars prequels would become a proving ground for ILM’s rapidly expanding digital animation capabilities.

Leading that charge was Rob Coleman, by then an animation supervisor at ILM. He found himself tasked with something the company had never fully tackled before: nuanced, verbal performances from fully digital characters who needed to share the screen – and emotional space – with real actors.

“It was all those things, plus we didn’t have a staff that actually had spent their time learning how to do nuanced performances,” Coleman recalls. He would tell director Joe Johnston for Light & Magic Season 2 that it was Dragonheart (1996) that really set the groundwork. “That was a huge leap for us. George was watching, and when he saw Dragonheart, he said, … ‘We are ready to go.’

“Most of the people at ILM had been flying spaceships and doing robots and maybe having dinosaurs smash around,” Coleman adds, “but they weren’t doing verbal performances where they were to hold their own with Natalie Portman and Liam Neeson and Ewan McGregor.” And to bring multiple CG characters like Jar Jar Binks, Watto, and Sebulba to life in Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), Coleman had to shift the team’s mindset. His growing team of 65 animators needed to think less like technicians and more like performers.

“We videotaped our actors so we had what they were doing physically, and we could look at them speaking to work out the lip sync. But pretty early on in Phantom Menace, I knew that I wanted to get into the subtext, not just the text. What’s going on inside the heads of the characters. If we could achieve that, we were gonna have believable performances, and the audience would have a connection with Watto, Jar Jar, Sebulba, and Boss Nass in that first film.”

The next major test came with Star Wars: Attack of the Clones (2002) and the digital resurrection of a beloved character: Yoda. Unlike Jar Jar or Watto, Yoda had already been established in the original trilogy as a practical puppet, sculpted by Stuart Freeborn and brought to life by puppeteer Frank Oz. Coleman’s team needed to preserve that legacy while updating the character with a broader range of expression.

“I went back and looked at Empire and it was nothing like I remembered because I’d grown up. It had changed what we expected,” Coleman says. “So what I was trying to achieve is what I remembered Yoda doing in terms of expressiveness and honoring how Frank moved him. Frank actually came by ILM, held up his hand, showed me the position of his fingers inside Yoda’s head. I had him pantomime some Yoda with me so I could see what he was doing.”

To ensure authenticity, Coleman and his team rigorously tested Yoda’s new digital incarnation. He recalls the moment he shared the first test with George Lucas. “There is footage of me presenting the first digital Yoda on the From Puppets to Pixels [2002] documentary. That is the real footage of me doing that, even though I asked the documentary not to shoot it. I’m so happy they did. I was really nervous, and I presented three speaking shots and three non-speaking shots on purpose because I was trying to show them that we could maintain performance without the crutch of dialogue. That was a focused decision because I knew from watching countless movies and TV, editors routinely cut to their action shots – the non-verbal reaction shot. I wanted to earn one of those, and we did.”

That approach paid off. One of Yoda’s most effective digital moments came not during a battle or speech but in a quiet reaction. “There’s a shot of Yoda in Palpatine’s office where Palpatine says something, Yoda’s leaving, and he turns, and he looks over his shoulder, and you can tell he doesn’t trust him,” Coleman notes. “And that’s all in facial performance, all keyframe, frame-by-frame animation. It ended up on the movie poster.”

Coleman’s work continued into Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005), by which point ILM had solidified its reputation as a pioneer in digital character animation. The scope of the prequel work, in retrospect, still feels enormous to the animation director.“I kind of got swept up in it all. Jim Morris [ILM’s general manager from 1993 to 2005] had put me forward for the role. Jim had taken me aside, and he said, ‘I think you’ve got the right temperament to work with George.’ So he sent me over … and dropped me off in London for a two-week interview with George Lucas, which I passed.”

Decades later, Coleman is reflective about the experience. Even as ILM continued to push forward in their abilities to mimic life, it was paradoxically the artists themselves that felt like the imposters. “Twenty-five years on, it’s kind of surreal to think back that I actually did that. I know that’s me. There are pictures of a younger me doing it. And I have all the memories, but sometimes it feels like it was someone else.”

Cursed Flesh and Living Tentacles: The Pirates Breakthrough

When Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) set sail, ILM faced a major challenge. Bringing the cursed crew of the Black Pearl to life wasn’t just about creating convincing skeletons – it was about making them believable next to live-action characters.

Hal Hickel, animation supervisor, explains to ILM.com that “It was a really complicated problem because the idea was that under moonlight these guys are skeletons, but in shadow, they’re flesh and blood.” Each shot became a complex blend of live-action photography and animation, requiring seamless transitions between the two. “You couldn’t just cut to them and show them in full skeletal form under neutral lighting,” he said. “It all had to be motivated by the lighting in the scene.”

The work paid off, but it was only the beginning. For the sequel, Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Man’s Chest (2006), director Gore Verbinski raised the bar with Davy Jones and his crew. These characters were fully digital – and fully expected to carry the emotional weight of their scenes.

Speaking about Bill Nighy’s portrayal of Davy Jones, Hickel notes that “Bill gave such a brilliant performance. We didn’t want to lose any of the little stuff. The slight squint of an eye, the tiny sneer.” Rather than relying solely on motion capture, the team blended Nighy’s reference footage with keyframe animation, ensuring that none of his subtle acting choices were lost. “We wanted the tentacles to feel alive but they had to support the emotion in his face, not steal focus.”

Animating Davy Jones’s tentacle beard posed its own technical challenges. “It was a mix of hand animation and simulation,” Hickel explains. “We animated parts of it for performance reasons, but we also let physics take over for the secondary motion, so it didn’t look fake or overly choreographed.” This approach required close collaboration between animators, rigging artists, and the simulation team to keep everything feeling realistic and responsive.

The complexity of Davy Jones and his crew pushed ILM to overhaul their pipeline. “We had to rethink a lot of how we built and rendered these characters,” Hickel says. Advances made for Pirates laid the foundation for ILM’s later work on projects like Transformers (2007) and The Avengers (2012).

Beyond the technical achievements, Pirates also marked a shift in how digital characters were treated on screen. As Hickel puts it, “It wasn’t just about creating spectacle. Gore trusted us to handle real character beats with these CG characters. It was an amazing opportunity.” Through a mix of performance, artistry, and cutting-edge technology, ILM helped create one of cinema’s most memorable digital villains. They had steered animation into entirely new waters.

The Leap to Full-Length Animation: Rango

After working with Industrial Light & Magic on three Pirates of the Caribbean films, director Gore Verbinski approached the studio with an ambitious proposal: to produce a fully animated feature. He had been particularly impressed by ILM’s work on Davy Jones and believed the studio could bring that same level of sophistication to Rango – a surreal Western populated by anthropomorphic desert creatures.

“We approached Rango the way we approach live-action visual effects,” visual effects supervisor John Knoll told Cinefex, “building out environments with a cinematic mindset rather than adhering to the rigid, modular workflow of conventional animated features.”

A defining innovation was the film’s approach to lighting and cinematography. Renowned director of photography Roger Deakins consulted on the project, bringing principles of real-world filmmaking into the animated space. “We lit Rango the way we’d light a live-action film, with practical principles of cinematography in mind,” Deakins told Cinefex.

ILM’s animation director, Hal Hickel, emphasized that they wanted the characters to inhabit their world with mass and texture. “We didn’t want our characters to feel overly polished or weightless,” he told Cinefex. “Gore wanted them to move with a slight awkwardness as if they truly existed in this dusty, unpredictable world.”

“He didn’t want to go head to head with Pixar or Disney or DreamWorks or Illumination. If they’re all over here, he wanted to go over there, aesthetically, in every way,” Hickel tells ILM.com. “Gore understood that the look of the film that he wanted to do was what we ended up calling ‘photographic.’ So not photoreal, but definitely not cartoony – the shot glass with whiskey in it, those kinds of things all had this patina of realism. So that seemed like a really good fit with us at ILM.”

Rather than using motion capture, Verbinski shot sessions with the actors performing together in a theatrical setting simply to inspire the animation. “It wasn’t about mapping motion one-to-one,” says Hickel. “It was about understanding the rhythm, the beats, the subtle mannerisms that would inform the final animated characters.” The result was a film that felt authored – visually distinct and emotionally resonant. For ILM, Rango marked another turning point.

“We knew this was an experiment,” said Knoll, “but we also knew it was an opportunity to redefine what ILM could do. Looking back, I think we did just that.”

Having left ILM before production on the film, Rob Coleman is still captivated by Rango. “It came about because John Knoll and Hal Hickel built a fantastic relationship with Gore Verbinski,” he says, “and they demonstrated to him through Pirates of the Caribbean that ILM had acting animators, and Gore is an actor’s director. They needed the right director with the right focus and the right mixture of talents and just bravado to say, ‘Yeah, we’re going to do this.’ And to hit ILM at the right time to make it, I think it’s still a marvel. I went back and watched it a couple years ago. It’s incredible what they did and what they achieved.”

“Every animator I know who worked on Rango had a ball and tells me continuously, ‘Gosh. Let’s get another Gore film going,’” says Hickel. “Yeah, they ate it up. He just really wanted people to feel like we were all filmmakers. You’re not the visual effects people up there, and I’m the filmmaker down here. We’re all filmmakers. We’re making this movie together.” That sense of collaboration was an ethos that ILM started in 1975 and continues to carry forward to this day.

Rango went on to win the Academy Award for Best Animated Feature in 2012.

Read more stories from our 50th anniversary series, “ILM Evolutions”:

ILM Evolutions: Pushing the Boundaries of Interactive Experiences

–

Jamie Benning is a filmmaker, author, and podcaster with a lifelong passion for sci-fi and fantasy cinema. He hosts The Filmumentaries Podcast, featuring twice-monthly interviews with behind-the-scenes artists. Visit Filmumentaries.com or find him on X (@jamieswb) and @filmumentaries on Threads, Instagram, and Facebook.