ILM creative director David Nakabayashi, along with artists from ILM’s global studios, including Aaron McBride, Cody Gramstad, Bimpe Alliu, and Chelsea Castro, reflect on the essential role concept art and storyboarding play in the filmmaking process.

By Jay Stobie

“ILM Evolutions” is an ILM.com exclusive series exploring a range of visual effects disciplines and highlights from Industrial Light & Magic’s 50 years of innovative storytelling.

From envisioning a look for cursed pirates to plotting out space battles, Industrial Light & Magic has an unparalleled reputation for working wonders in collaboration with filmmakers to bring the stories they envision to life. Built on a 50-year legacy of talent and tenacity, ILM’s Art Department has grown into a global hub for generating and executing the ideas that immerse audiences in the worlds they see on screen. In this installment of ILM Evolutions, we’re heading back to the drawing board to focus on conceptual art and storyboarding, as this indispensable imagery fuels the creative process by visualizing a filmmaker’s ideas in the earliest stages of production.

ILM Art Department creative director David “Nak” Nakabayashi sat down with ILM.com to share his insights on the history of concept art and storyboarding, as well as his own first-hand knowledge of the craft. With an esteemed resume featuring iconic films such as The Hunt for Red October (1990), Jurassic Park (1993), Men in Black (1997), Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999), A.I. Artificial Intelligence (2001), Avatar (2009), Star Wars: The Force Awakens (2015), and many more, Nakabayashi now oversees art directors, illustrators, and artists across ILM’s global studios. Additionally, artists Aaron McBride (San Francisco), Bimpe Alliu (London), Cody Gramstad (Sydney), and Chelsea Castro (Vancouver) joined the conversation to highlight their careers and the latest developments in their field.

Ideas and Intentions

Concept art and storyboards each serve unique purposes in the production pipeline. “Concept art depicts a scene, setting, place, location, robot, spaceship, weapon – they initially come from the script along with a brief description,” outlines Nakabayashi, who emphasizes the extent to which the art helps the crew visualize the project they will be creating. “These are the key beats in the film. Concept art establishes what we’re going to be doing. We’re showing everyone that this is the movie we’re going to be making when absolutely nobody has any idea what it will look like.”

Nakabayashi cites concept artist Ralph McQuarrie’s contributions to Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) as the perfect example of such art having an inspirational impact on a film. “They based everything on his art. It fed everybody’s imagination.” Today, concept artists regularly assist filmmakers as they design and seek green lights for their films. “Sometimes, ILM will do development or spec work, where we take concept art and show the studio what the movie will be with the same intention as Ralph did. We carried that on.”

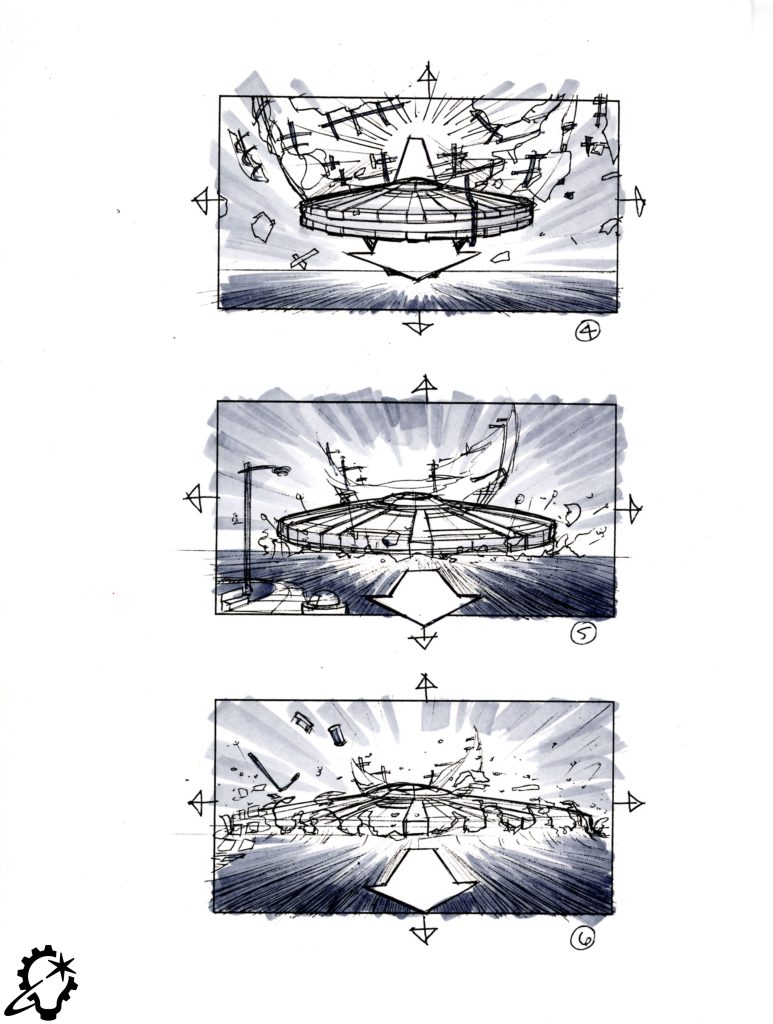

While concept art focuses on design, storyboards define the action that occurs on-screen. “Storyboards are all about the cinematic motion, the energy of a visual effects shot. That’s why ILM’s Joe Johnston was such a great foundation for this department. He would draw storyboards with arrows that would be compressed in perspective, and you really understood the depth of what he was trying to say,” Nakabayashi notes. Over time, the advent of digital animatics altered the use of storyboards. “We hardly storyboard anymore these days because animatics act as the filler, but it’s the same principle.”

From a broader perspective, Nakabayashi is quick to point to the artistic value of concept art and storyboards. “A pencil drawing, for me, is as powerful as a Ralph McQuarrie gouache painting. I get consumed by the techniques sometimes, and how a person can draw this perfect angle of a little spaceship cruising through the columns of some weird planet. To draw that sequence helps the director make decisions. It’s about visualizing and timing the film before they actually shoot anything, though it’s all changed quite a bit with the whole animatics tool set.”

The Importance of Art

“When you look at the scope of what ILM has done,” Nakabayashi says, “obviously Star Wars was a flashpoint for concept art and storyboards because that was the first way of getting creativity into the movie and bringing visual life into the script.”

Of course, the benefits extend far beyond what is seen on-screen. “Art is important for many other reasons,” Nakabayashi explains. “For ILM, it is also about the budgeting process. Historically, the model shop would look at storyboards and concept art and have an idea of what was coming. Production is very budget-driven. ILM would storyboard their sequences, not just for the artistic impression of it, but for logistics and production. That was how a director would communicate with the visual effects supervisor. ‘We’re going to shoot this practical and this blue screen. We can save a lot of money if we do this with miniatures.’”

Nakabayashi boils the work down to its essence, relaying, “It’s about the artists believing that the future is possible and the creation of the cliche ‘Show me something I’ve never seen before,’ which is sort of a byline we usually get from our clients. We can do that because we have the right people – people who take inspiration from the artists who came before them. That’s ILM’s culture of concept art and storyboarding. I’m not a great storyboard artist, but I can communicate and do the work. To me, that is the most important part – communicating the ideas.”

Communicating Concepts

As an art director at ILM’s Sydney studio, Cody Gramstad (Sonic the Hedgehog 3 [2024]; Lilo & Stitch [2025]) affirms the significance of communication, stressing, “When it comes to being a concept artist, you’re not necessarily there to create artwork. You’re there to clarify and communicate ideas. My favorite part of the job is actually the conversation where I sit down with a bunch of creative people, brainstorm potential solutions to problems, and get everyone amped up as we figure out our creative direction. Painting and visuals are a part of that, but being able to talk, pitch ideas, and get people excited is one of the most important skill sets.”

Gramstad, whose parents were professional sculptors, takes the notion a step further, suggesting that prospective concept artists can bolster their abilities by balancing the dedication necessary to hone their craft with time off for real-life adventures. “Step away from your computer every now and then, have some experiences, meet people, and socialize,” declares Gramstad, placing value on the correlation between communicating ideas and relating to those around you. “It’s a lot easier to work with someone who has gotten out in the world and brings those stories into their artwork.”

The ILM Influence

Turning to Industrial Light & Magic’s unique place in the history of concept art and storyboarding, Nakabayashi states, “ILM is special because it all sort of started here. It’s special because of the people who believed and put their foot down – Colin Cantwell, Ralph McQuarrie, and Joe Johnston. There were others on the outside, like Syd Mead and Ron Cobb, all these illustrators who were doing sci-fi stuff, but ILM was the first one to take the visual effects art department and make it something that everybody wanted to be.”

San Francisco-based senior art director Aaron McBride notes ILM’s post-Star Wars permanence as a standout achievement for the company. “Before ILM, visual effects departments would start up for the duration of a film and be temporary. When the film was over, everyone would get scattered. It was almost nomadic,” McBride mentions. “There was a demand for the work that ILM was doing, and ILM was able to advance technologies because it was kept intact.”

By the time of Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983), Nakabayashi explains that directors began approaching ILM for innovative films like Poltergeist (1982), The Goonies (1985), Cocoon (1985), Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991), and many others. From crafting concept art that gave those films their “first breath of life” to “feeding production with ideas,” Nakabayashi views the ILM Art Department’s past with distinction. “Historically, we’ve had some of the best concept artists ever – Doug Chiang, Harley Jessup, John Bell, Terryl Whitlach, Christian Alzmann, and James Clyne. A lot of the artwork that they created determined whether or not a movie was made. That kind of talent, to me, is the greatness of the department.”

As the visual effects art director on The Phantom Menace, Nakabayashi saw connections between his work and that of his predecessors. “We had all this concept art, and part of my job was to bring it into the real world. That’s what the ILM Art Department has always been at the forefront of back to the days of Joe Johnston because he wasn’t even a storyboard artist when he started. He also got into the model shop and built models. He loved making miniatures and setting up the stage. It was kind of the birth of the visual effects art director. We followed along that path. It’s not just doing the drawing or coming up with an idea, it’s implementing it, as well.”

Executing the Ideas

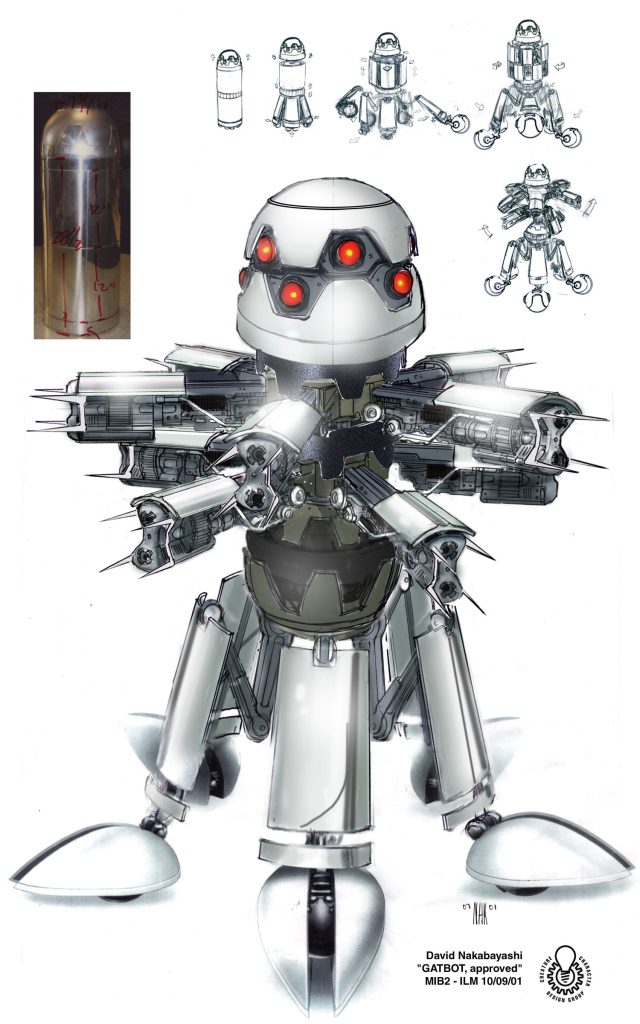

Nakabayashi recalls his experience collaborating with director Barry Sonnenfeld on Men in Black II (2002). “I was tasked to take a trash can and turn it into a killer robot. I liked the idea that it opens up like a flower, and it comes with multiple gun turrets that are not necessarily normally situated in a standard military platform. Maybe it’s more like an orchid. With a few changes, the design went to computer graphics, and I helped develop it in dailies with the modelers, painters, and animators.”

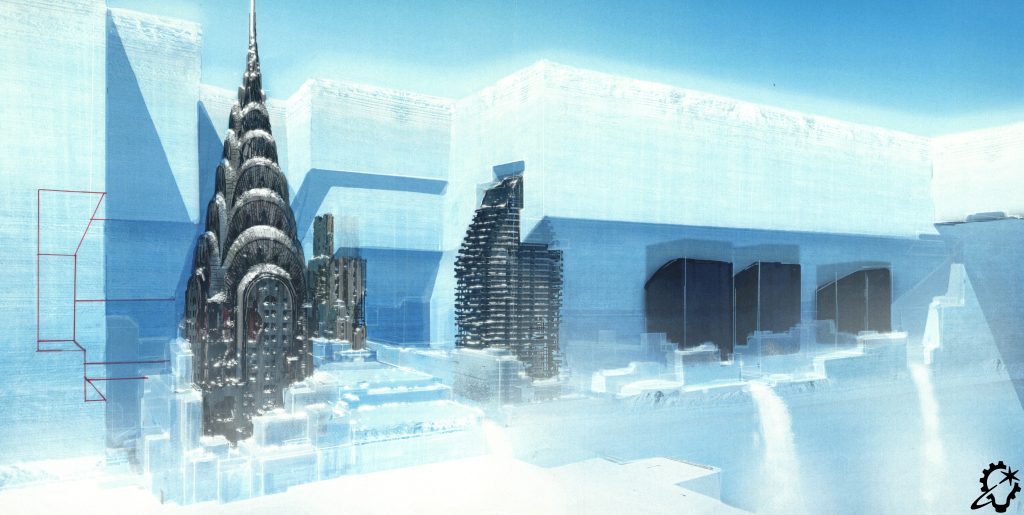

Turning to his time on A.I. Artificial Intelligence, Nakabayashi posits, “Those worlds – Coney Island, the Rouge City, an underwater theme park – were all absorbed through storyboards that Chris Baker did with Stanley Kubrick for a couple years. We started with that as our inspiration, and then we started doing colored artwork – paintings, drawings, some storyboards for shot ideas – and pitched those to [visual effects supervisor] Dennis Muren and numerous other people. It became this whole world of miniatures, and it was also on the brink of the digital component coming into the workflow. There’s a real marriage of practical effects, which I will still say is the most fun to work on, with the digital component.”

Envisioning new worlds still requires references that ground them in reality. For The Phantom Menace, Nakabayashi saw a dry South Dakota riverbed as a perfect reference for the bottom of Naboo’s oceans, proposing a fresh take on how to approach the Gungan city to Dennis Muren. “I go, ‘What about a booming shot? You track over and dip down to see the top of the city as opposed to always looking up. We’re going underwater, right?’” Such insight and inspiration impressed director George Lucas. Nakabayashi touches on the Gungan shield that comes down on the battlefield, continuing, “I had this idea – it was a parasol and an umbrella, kind of like a sprinkler. George loved it.”

Turning the Tide

As is often the case with the work ILM tackles, changes manifested for the art department over the years. Nakabayashi indicates Adobe Photoshop – the editing software co-created by John Knoll, ILM’s current executive creative director and senior visual effects supervisor – as technology that revolutionized his field. ILM even dabbled with Photoshop during its earliest days. “With Death Becomes Her (1992), Doug Chiang took plates and drew the effect of Madeline Ashton [Meryl Streep] having a broken neck. He took pictures of people and we altered them into these effects-type things.”

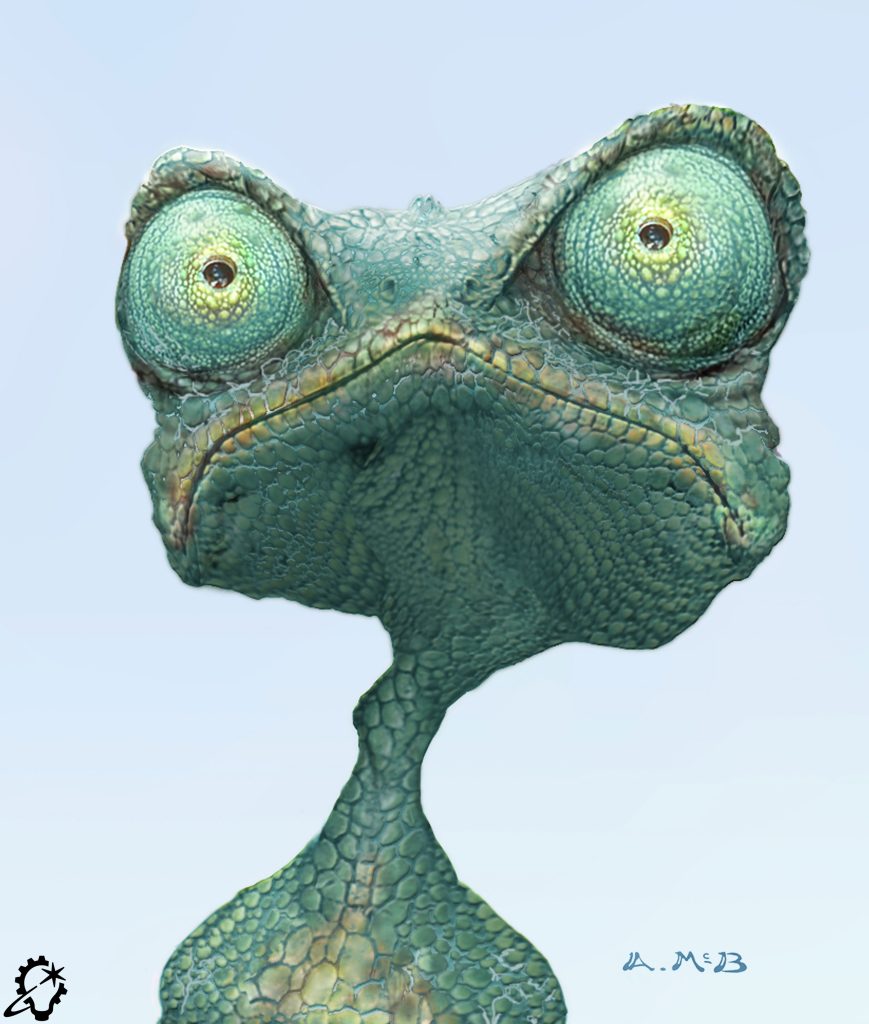

Along with Photoshop’s availability, concept artists continued drawing with traditional tools like pencils, markers, and paper until ILM received the call for Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl (2003). “The director, Gore Verbinski, was like, ‘These are great drawings, but I want to see what it looks like in my film. Don’t give me a pencil sketch,’” Nakabayashi says. The filmmakers wanted a desiccated – but not bloody or gory – aesthetic for the cursed pirates, so Aaron McBride test-photographed beef, turkey, and salmon jerky.

“The turkey jerky felt the best because it scattered a slightly lighter color and was the closest to the right muscle striation texture,” muses McBride, who credits his shyness at speaking up in dailies for the process, laughing, “I pushed to do the concept art as photo-realistically as possible mostly because I wanted to be able to point to the art and not have to say anything.” As Nakabayashi explains, “Aaron took a plastic skull, a bunch of costumes, and turkey jerky, scanned it, and put all these textures on the face. This gave Gore a direction for his movie, and it was a huge moment. Everybody was trying to copy Aaron after that. We still drew and did other traditional methods, but all of a sudden, everything had to be photoreal.”

Another Dimension

“Getting photoreal is a lot easier now with three-dimensional tools,” Nakabayashi adds. “A quick sketch might happen, but a lot of our artists are excellent at building and designing 3D packages. It’s a great transition point from concept art to visual effects work, because of the digital assets.”

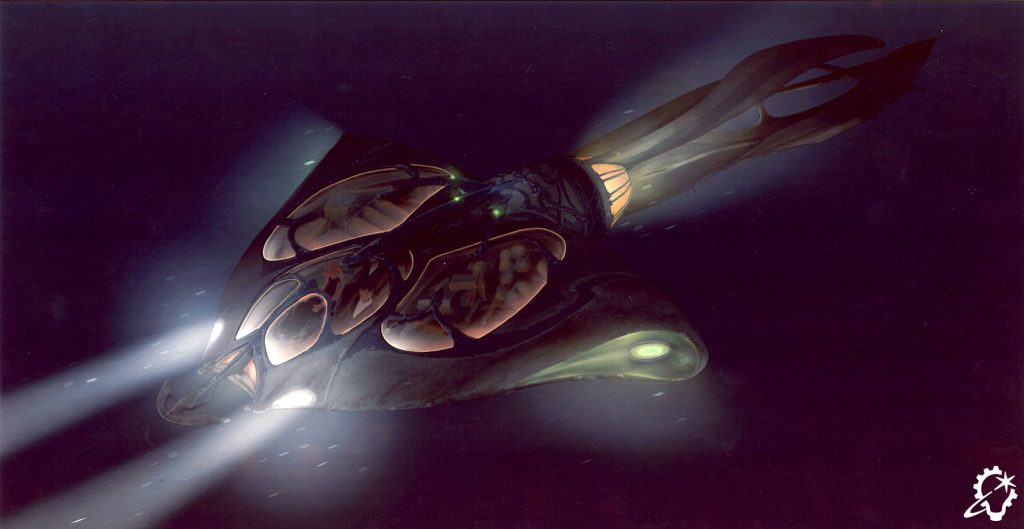

As an intern, one of McBride’s first jobs actually involved developing photos taken for The Mummy (1999) and scanning them into a computer to be painted. He later experimented with 3D on Star Wars: Revenge of the Sith (2005), and then leaned into it while working on the suit-up machine in Iron Man (2008). “I didn’t have the skill set to do mechanical drawings, so I blocked it out in 3D to figure out how some of the panels and other mechanical things moved,” chronicles McBride. For The Avengers (2012), McBride designed a snake-like creature that dropped soldiers into the Battle of New York. Inspired by the Greco-Roman aesthetic crafted by the Marvel art department, McBride envisioned the troop transport “as a Roman galleon, almost like a biomechanical being, which had fins that were like oars.”

“We have a couple artists in the department who are sort of hybrid artists,” remarks Nakabayashi. “They do 3D, 3D animation, compositing, and things like motion graphics. Sometimes, we want to bring a flat, still drawing to life, and you’ll do a quick projection. Making something move is a huge component for success in your pitch meetings. The animatics these days are so good and so accurate that you can’t deny the distinction. They’re more productive than storyboards.”

A Generational Shift

Having contributed to a variety of ILM projects as an art assistant, Chelsea Castro is now making her mark on the next wave of ILM shows as a junior concept artist at the Vancouver studio. Castro, who finds inspiration for her art in everything from books to video game soundtracks, strikes a balance between traditional methods and cutting-edge techniques. “Coming from a 2D background, I tend to sketch as much as I can, and then move on to photobashing [combining photographic and CG elements together into a new piece of art] and texturing,” Castro shares. “Afterwards, I fully build out as much as I can in the 3D software that I’m using. Then I go back into 2D to tweak everything and finalize them.”

Castro sees a fundamental evolution when it comes to storyboarding, explaining, “I feel it has gotten a lot more immersive. We still do the classic line art, but now that you can build whole 3D worlds, I’ve seen storyboards done completely in 3D. Sometimes the artists take their scenes and show it to the client with different cameras set up, like it’s their own film set. The game has changed, but the spirit of it is very much the same,” Castro concludes. “Brainstorming and getting ideas out is great with the new technologies. The refinement is where you fall back on your foundations, techniques, and the skills that you’ve built up.”

Cody Gramstad adds, “3D gets you closer to real-world accuracy. Inherently, as we’re hand-painting things, we have a tendency to make artistic cheats. It’s not necessarily a bad thing in illustration, as we can push that to enhance emotion. But, especially in a live-action context, reality is what makes the world believable – 3D is very useful for that because it takes calculations from the real world. For example, how lighting actually bounces off of different surfaces.”

Bimpe Alliu from ILM’s London studio observes that increased accessibility to 3D software among young people is as vital as the technology itself. “I’ve mentored teenage students who are learning 3D, picking up software like Blender, and learning to model and sculpt,” Alliu details. “Regardless of the gradual transition from hand-drawn paper storyboards to digital storyboards, as well as individual artists’ preferences for 2D or 3D drawing, a combination of those skills are always used to do the work to the best of your abilities,” Alliu asserts. “More people are using different techniques in order to bring together their storyboards. It’s harmonious.”

A Global Approach

As the ILM Art Department’s creative director, Nakabayashi embraces the modern tools bringing our world closer together as he oversees and collaborates with artists at ILM’s international studios. “I’m very much hands off, and I let the artists do their job,” opines Nakabayashi, who jokes, “When something goes wrong, I get called upon.”

For Cody Gramstad, being an art director in ILM’s Sydney studio means handling multiple shows simultaneously. “I meet with visual effects supes and give guidance for the shot sequences and how they’re progressing, and at the same time, provide feedback to the Sydney art department team to guarantee they are targeting the supervisors’ and directors’ goals.” Gramstad points out that the process is often a worldwide effort, regularly involving colleagues at ILM’s other global studios. “We support each other and make sure that we’re getting the work done at the level we need to. Nak and [director of art and development] Jennifer Coronado make certain that standards are equal across the different studios.”

However, informal conversations are just as productive. “There are a lot of art posts and chats. Keeping people inspired becomes really important, and it’s great to have artists around you that can contribute to that. Sometimes, we do design competitions, too,” Gramstad proclaims. “The art directors also sit with the artists every couple months. We break down where we can improve and how to adapt our approach as we move forward on future tasks. There are so many different shows across the world, so they’re all learning different lessons. It takes direct communication to make sure those lessons get spread to all of our studios.”

Timelines and Tasks

With video calls continuing to bring our world closer together, ILM’s concept artists are able to communicate with clients and take on projects across multiple continents while working from their respective spaces at ILM’s global studios. This ability allows artists to be flexible in terms of their involvement on any given series or film. “Sometimes, we can be on a show for a day,” says Bimpe Alliu, who estimates that the longest time she spent on a project was her two-year tenure on The Marvels (2023).

Similarly, the timeline is naturally impacted by the stage at which the artists are brought on. A fan of anime who started out by drawing her friends as Dragonball Z characters in her youth, Alliu elaborates on the depth of her tasks, advising, “It can be pre- or post-production. We can be working on plates or creating assets for ourselves. With a recent character design, I was given the previs model and a scan of the actor, so I took those, mishmashed them together, and then detailed the clothes on top of that.”

Watching Iron Man inspired Alliu to pursue her current career, so working on WandaVision (2021) was a full-circle moment for the self-described “massive nerd.” “For the sequence where The Vision is disintegrating, I was designing what the disintegration effects would look like. Not just the space, but also The Vision himself,” Alliu recounts. On ABBA Voyage (2022), Alliu was brought on so early that she “was designing what the room where ABBA themselves would be recording and filming all their motion capture stuff would look like. I even designed baby dragons for a TV show called Lovely Little Farm (2022). They made them into little maquettes, so that was the first time that anything I designed got made physically.”

A Legacy Earned from Lessons Learned

Despite all the changes that have transpired with concept art and storyboarding over the last half-century, ILM’s history and prestige set it apart as it moved into the present and looks to the future. “ILM has a support structure and legacy that a lot of other studios don’t have. ILM can nudge newer people in the right direction as they learn the lessons that their predecessors have discovered in the past,” Gramstad reveals. “There’s also the sheer amount of variety at a place like ILM. Since so many film studios come to ILM as a source of visual effects experience, we get a huge range of projects. So, more so than any other studio in the world, I think that ILM allows people to be super versatile. One morning, we’ll be working on animated silliness with Sonic the Hedgehog, and two hours later, we’re doing a grounded oil rig on an ocean that has to be absolutely photorealistic.”

ILM’s academic aura benefits its up-and-coming and veteran personnel equally, as Bimpe Alliu resolves, “You don’t have to be the finished article. You’re going to constantly grow, and ILM is always looking for potential. It helps when you’re around people that you can learn from.” Chelsea Castro beams, “At ILM, you feel so included, and everyone shares their time with you. It’s amazing to have access to all these people around the world.” Aaron McBride, who has been with ILM for 27 years, praises ILM’s multi-generational nature for making him a more well-rounded artist, concluding, “New techniques can inform older ones, and older techniques can inform new ones. I’m inspired by what younger artists are doing, and I think it’s important not to dismiss any aesthetic because it’s new to you.”

—

Jay Stobie (he/him) is a writer, author, and consultant who has contributed articles to ILM.com, Skysound.com, Star Wars Insider, StarWars.com, Star Trek Explorer, Star Trek Magazine, and StarTrek.com. Jay loves sci-fi, fantasy, and film, and you can learn more about him by visiting JayStobie.com or finding him on Twitter, Instagram, and other social media platforms at @StobiesGalaxy.