After 38 years, the veteran effects artist is retiring.

By Lucas O. Seastrom

First opening in 1987, the original Star Tours attraction at Disneyland included what was the most complex optical composite created at Industrial Light & Magic up to that time. A “view” out the window of a starspeeder was in fact a state-of-the-art flight simulator developed by Walt Disney Imagineering (WDI) and Rediffusion Simulation with miniature effects by ILM. Among the thrilling encounters for passengers onboard was a harrowing trip through a cluster of icy comets which the crew dubbed “ice-teroids.”

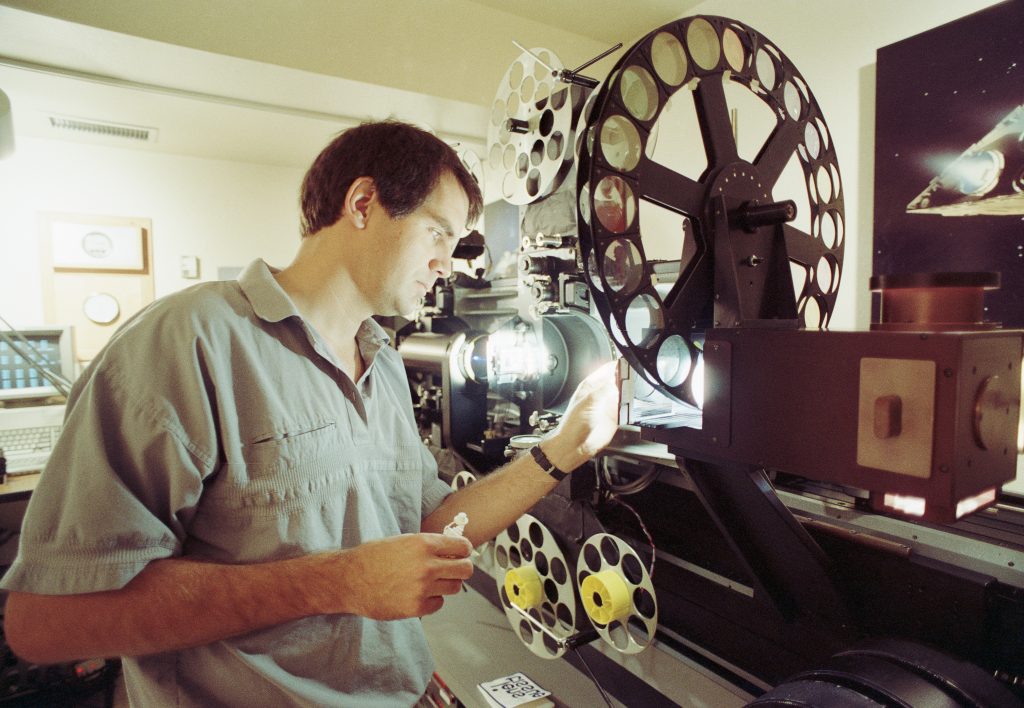

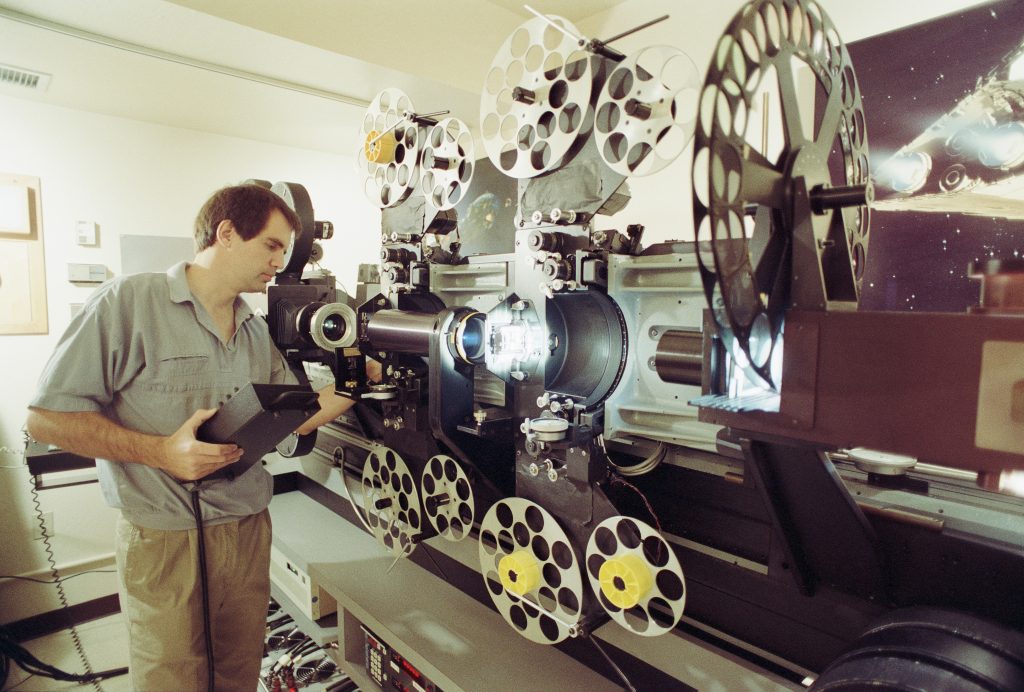

Compositing in this photochemical era involved a piece of equipment known as an optical printer. With iterations dating back to the earliest days of cinema, optical printers combined separately-photographed elements by recapturing them – one frame and one layer at a time – onto a new roll of film negative. Optical printers and the artists who operated them created the final effect one viewed onscreen with everything carefully (and painstakingly) blended together. Going back to Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), ILM had developed the most sophisticated compositing techniques yet seen, allowing for even greater refinement and finesse.

The ice-teroid shot in Star Tours combined some 60 elements of individual sections of film. By comparison, the most complex shot of a space battle in Star Wars: Return of the Jedi (1983) just a few years earlier had little more than half the number. One of the two optical printer operators to work on the new shot for Star Tours was Jon Alexander, hired only that year in 1986.

“Don Clark and I worked on the shot together on the Anderson Optical Printer,” Alexander tells ILM.com, “and once you started, you couldn’t stop. Once you started a shot all the motors warmed up and they needed to stay on. If they were turned off you risked the machine cooling down and settling into a misalignment of the earlier passes. It took 24 hours to make all the elements so we split 12 hour shifts.

“The Anderson was an old-style optical printer,” Alexander continues, “where if you wanted to add any movement to the shot you had to crank little knobs by hand with an accuracy at best of a couple hundreds of an inch. Some years later ILM acquired the MC [motion-control] printer which was accurate to within a couple ten-thousandths of an inch, which is crazy. It’s like throwing a baseball from here in San Francisco and hitting the Empire State Building in New York.”

38 years later, Jon Alexander has now decided to retire, and ILM is celebrating his storied tenure with the company that stretches over dozens of films, series, attractions, and special venue projects – not to mention quite a lot of technological change.

Back in the late 1970s, Alexander had what he calls “a wandering college career” while studying at Ohio State University. With a background in both engineering and cinematography, he arrived in Southern California in 1980 to work at Calico Creations, an active commercial house. There, Alexander gained experience with motion-control camera systems, innovative tools that combined the latest computer technology with mechanical engineering. “This was before personal computers were readily available,” he notes. “We were doing programming with machine tools to create motion graphics for around 50 commercials a year. Everyone wanted something like 2001: A Space Odyssey [1968], the slit-scan style. It was a very manual process.”

These tools were used for everything from photographing miniatures to shooting hand-drawn cels on an animation stand. In conjunction with the team at Calico was Bill Tondreau, an accomplished engineer who designed his own motion-control systems, which Alexander learned to use.

“The system that ILM used on Star Wars was very analog,” Alexander explains. “You could speed up or slow down, but it was very hard to hit specific points. It was an art for those guys to get used to. They were flying in space so it didn’t have to be as precise. They got really good at it, but it wasn’t as adaptable as what Bill Tondreau later developed, which used stepper motors. ILM was switching over to this style, and my colleague Rob Burton at Calico was hired by ILM for Howard the Duck [1986], and they had so much work that they needed more operators. They had to be Tondreau-system operators, so they recommended me. They were looking for someone to do this specific thing, and hired me for three months. I have milked that for 38 years.”

Initially, Alexander worked in the animation department, photographing cels with a down-shooting system. Among these projects was The Witches of Eastwick (1987), for which Alexander shot a tennis ball as a lone element for a scene involving a doubles match. This was required because, as Alexander recalls it, only the actress Cher knew how to play tennis, so the cast mimed the game without a ball.

“It was while working on this camera for Eastwick that I met Michael Jackson,” Alexander says. “I was working late and no one else was in the back of D Building [at ILM’s Kerner facility]. I was leaning over and adjusting the tennis ball when I got this feeling someone was right behind me. I turned my head and he was about three feet away with two of the biggest men – security guards – I’d ever seen. [Producer] Patty Blau popped around the guards and said, ‘Hi, this is Michael. He was wondering what you were doing.’ This was around the time ILM was finishing up [Disneyland attraction] Captain EO.”

Alexander’s technical experience once again necessitated a move, this time to the optical department, where a new optical printer was being refined. The aforementioned “MC,” or motion-control printer had been developed by Los Angeles-based Mechanical Concepts as a first of its kind device.

“It was a motion-control printer, but when it got here, it didn’t work,” Alexander explains. “Everything was project to project in those days, but optical was always going and it looked like they needed more folks. When I heard about this new printer, I went up to Kenneth Smith, who was running optical at the time, and explained that I could put a Tondreau system on it. I had done some optical work in L.A., so it wasn’t entirely foreign, but ILM was off the charts in terms of the people and equipment they had.”

Alexander collaborated with machinist Udo Pampel to reconfigure the MC printer to run on the system. The result was arguably ILM’s most sophisticated optical printer that allowed artists to create not only incredibly precise composites, but recreate shots entirely by adding movements or zooms. An early assignment for the Academy Award-winning Innerspace (1987) required Alexander to simulate the bouncing undulations of the camera “inside” the body of actor Martin Short.

“They were cutting back and forth between Martin Short running and this smooth motion-control inside the body, and [visual effects supervisor] Dennis [Muren] thought it looked weird,” Alexander says. “But at that point they couldn’t go back out on stage and reshoot everything. Dennis asked me if I could do something that had the same up and down motion of running. It was a tough thing to do on the stage, but it wasn’t particularly tough on the MC Printer because I could project onto the wall, track something specific like a button at the center of his chest, which then provided a curve like someone running along. So when I did the composite, it matched up. It was no problem to do that because of the way the printer was set up. I used to do a lot of that kind of match-moving stuff to project onto the wall and track something in a minute way. That’s entry-level now, but to do that in post at the time was almost impossible because there were so few motion-control printers around. We had one of the first.”

As Alexander notes, for a handful of years, his position was among the most significant in ILM’s pipeline, considering that most everything had to be funneled through the MC printer. “Looking back at these things, it wasn’t a big deal to accomplish,” he admits. “It was just that people hadn’t done it before. Supervisors like Dennis or Ken Ralston could expand what they wanted to do creatively, and people like me were a great set of hands to help them.”

Change was in the air, however, and computer graphics (CG) effects were steadily on the rise. At a time when many traditional artists and technicians were making decisions about whether to embrace the change, Alexander lept in headfirst. “At that time, there were no BFA’s in computer graphics,” he explains. “You had to come out of an engineering school just to do anything. It fostered this new kind of collaboration. We on the film side knew what the final product had to look like and the programmers knew the math and physics to make it possible.”

Alexander remains very matter-of-fact about the transition. “CG helped eliminate the painful aspects of working on film. You’d work for hours on something, moving and adjusting things. It was so choreographed that you had to put the filters in the exact same order each time to get the same result. Then after you shot it, you’d go to the dark room, turn the lights out, unload the magazine and put the film in a can, and then you’d turn the lights on and realize you’d forgotten to close the can…and what you just shot was gone. In CG, if you make a mistake, you press ‘Undo.’”

Among Alexander’s first CG projects were Fire in the Sky (1993), The Flintstones (1994), and Forrest Gump (1994). A personal standout shot came in 1998’s Meet Joe Black when he had to help create the shocking death of actor Brad Pitt’s character, a young man who is hit by two cars while crossing a street. “They shot the different elements with bluescreen,” Alexander says. “The cars came in slow because it was too dangerous to go fast and I timed everything to match it all together. The director [Martin Brest] asked to make him flip in the air, which I then did.” A compositing supervisor at that stage, he enjoyed the opportunity to “test things and try out ideas,” from large elements to minuscule details.

Alexander’s last major shift came around 2008 when visual effects supervisor Bill George organized a unit to assist WDI with a reimagined Star Tours, ultimately opening in 2011 with 3D digital imagery. Eventually, Alexander stayed with George’s rides unit full-time, contributing to everything from Disney’s Soarin’ Over the World and Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance to Universal’s Race Through New York Starring Jimmy Fallon. In every case, he was able to work in a diverse array of image and presentation formats. More recently, Alexander has contributed to special venue projects for the Sphere in Las Vegas, including Dead & Co.’s Dead Forever concert series (2024) and Darren Aronofsky’s Postcard from Earth (2023).

“The Sphere is like being in a VR headset but massive,” Alexander says. “Something like 17,000 people can interact with the screen at one time. I was talking with Darren Aronofsky about how it opens up the possibilities about how to tell a story. You no longer set the direction for people to look. Something could be going on in one area, and then you put something up in another area. Maybe some people notice and others don’t. It’s a different way of thinking about it, like in a game, where you influence the way the story goes. To me, it’s really cool to move into this new space where you’re not limited by being in a movie theater where you can only look in a certain direction.”

As his ILM journey comes to a close, it’s poignant to consider that Star Tours in particular has formed bookends to the many productions Alexander has been involved with. In fact, he and Imagineer Tom Fitzgerald are the only two people to have worked on every iteration of Star Tours to date. Just recently, Alexander spent six months with WDI to help oversee the installations of the ride’s latest update in Disney Parks in California, Florida, and France. With characteristic humility, he’s keen to point out that he made a small mistake way back on that fabled ice-teroid shot in the original 1987 version. A matte for one of the dozens of ice-teroids was slightly misaligned, a detail too small for most viewers to even notice, but something that Alexander’s children would never fail to mention, much to his own amusement.

“I came into this with different expectations, like we all do,” Alexander reflects. “You think they’ll write a book about you one day. No one’s going to write a book about me. Then you think, maybe I’ll get a chapter in the book. But most of us just become footnotes. We’re part of a team. My dad and my uncles were all sergeants in the military. I got an appointment to the Air Force Academy. When I went there for induction a just-graduated 2nd Lieutenant was showing us around, and the Master Sergeant came by, an older guy with the stripes on his arm, and gave a crisp salute to this new 2nd Lieutenant as he walked by.

“The Lieutenant said, ‘There’s a lesson for you,’” Alexander continues. “‘This guy has to salute me because I’m his superior officer, but he’s a sergeant and he does everything. I can’t do anything that he does. He organizes all of the enlisted men to do what we need, so I have to listen to him and trust him to get it done.’ I kind of feel like I’m a Master Sergeant. I’m fortunate enough to have gotten to the point where I’m involved at this level, and I feel like there’s not a shot that I can’t fix. It’s not just me; it’s my position. That’s what a compositing supervisor is supposed to do. If there’s a shot with a problem, and you can’t go back and change anything, yes I can fix it for you. I find that particularly gratifying. I’ve stayed at this level in part because it’s about life-balance. If I were to go higher, I’d be away for four months at a time, and I didn’t want to do that to my family. I’ve got like five Oscars on the family side of stuff.

“George Lucas chose people really well, and those people chose their hires really well,” Alexander concludes. “George trusted people like Dennis Muren to get anything done for him, and Dennis trusted people like me to get him whatever he needed. George and Dennis and those types of people were magnanimous enough to let people like me in the room. Because of that, I’ve tried to share as much as I can when new folks come in so they feel like they’re part of it. To me that’s the most important thing, making people feel like they’re part of a team. The beauty of this place has been how collaborative it is.”

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.