ILM’s Sydney studio took on everything from digital creatures to CG environments for this adaptation of a beloved Disney Parks attraction.

By Lucas O. Seastrom

For nearly 40 years, Industrial Light & Magic has had a close relationship with Disney Parks. They have not only created visual effects for attractions themselves, from Captain EO and Star Tours in the 1980s to Star Wars: Rise of the Resistance and Guardians of the Galaxy: Cosmic Rewind in recent years, but have also worked on feature film adaptations of attractions such as Pirates of the Caribbean: Curse of the Black Pearl (2003) and Jungle Cruise (2021).

2023’s Haunted Mansion is another adaptation of a beloved attraction, which first premiered at Disneyland in 1969 and later at Walt Disney World in 1971. Director Justin Simien brought distinctly apt qualifications to the project, having worked as a Disneyland Resort cast member during his film school days at Chapman University. “Whenever I was in Disneyland, it was like being inside of a movie,” he tells ILM.com. “I would go on the rides over and over again, and I’d get chills in the same spots and catch my breath in the same places. I realized that this was cinema. It’s a theme park that’s physically happening around me, but the tools of the trade are the same.

“There’s production design, sound design, lighting, dialogue, character, and story,” Simien continues. “It sounds like something you’d say in a press interview, but it’s true – I remember going on The Haunted Mansion and Pirates of the Caribbean and thinking, ‘I need to figure out how to translate this to what I want to do as a filmmaker.’ Walt Disney and his artists brought us into these fantasy places. That’s the art. That’s the thing I needed to figure out. So for me, it all felt very complementary. Working at Disneyland was just another way of escaping into the movies.”

Simien’s approach to bringing Haunted Mansion to the screen was as complex as the vision of the attraction’s original creators. “I was really fascinated by the constant conversation that the Imagineers had about how scary it should be or how funny it should be,” Simien comments. “It was such an interesting way to make something unique. It’s not horror in the traditional sense. You’re not walking through a haunted house at Universal Horror Nights or something like that. But it’s not straightforward Disney either. It’s very subversive and there’s a lot of hidden, kind of dark stuff going on.”

Simien and his team were able to visit the Disneyland Haunted Mansion in the off-hours, where current Imagineers helped them to understand its distinct narrative brilliance. “When you’ve made your way up through the Mansion, you’ve turned a corner, and you’re looking down into the dining room,” Simien explains. “All of the swirling dancing ghosts are there and ghost heads are coming out of the organ. It’s a culmination of all the different effects in the ride, the Pepper’s Ghost effect in particular. Even as an adult, when I know how it’s done, it takes my breath away. There are a couple of moments in the movie where we’re working from the same point of view. We pay homage. The ride has this build-up with specific timing and pacing.”

Simien took his cinematic leads from works in the 1980s and ‘90s, such as Ghostbusters (1984) and Little Shop of Horrors (1986) and the films of Tim Burton. He also went back to source material shared by the Disney Imagineers, including Robert Wise’s The Haunting from 1963. “There are so many parallels in the production design of that movie and the attraction,” he notes. “You see very subtle elements in our movie that are like that. There are slanted mirrors and shots where you look through a doorway and it’s a kind of off-angle. You get a claustrophobic ‘things are not right with the world’ feeling without really doing anything, just designing things a certain way.”

From a visual effects standpoint, Simien envisioned a mix of practical and digital techniques. “I wanted as many practical effects as I could get,” he says, “which I knew was always going to be a battle [laughs]. The movie is so fantastical. This wasn’t a typical horror movie where you hide the monster. It’s a Disney movie. There’s an expectation that you’ll get to see the ghosts. I wanted them to have a physicality, to be people in make-up and costumes moving on wires. We needed to ground the movie as much as possible in those things.”

ILM was one of multiple effects vendors on the project, and initially planned to contribute a modest sum of around 400 shots, overseen by Sydney-based visual effects supervisor Bill Georgiou and visual effects producer Arwen Munro. American-born, Georgiou spent nearly 15 years at Rhythm & Hues, climbing the ranks from rotoscope artist to compositing supervisor and sequence supervisor. He later worked as the onset visual effects supervisor on the DisneyXD program, Mighty Med, before joining ILM and moving to Australia in October 2021.

Coincidentally, Georgiou was an apt choice for Haunted Mansion, having known production visual effects supervisor Edwin Rivera for many years at Rhythm & Hues, not to mention Justin Simien himself. They had met through a mutual friend, editor Phillip Bartell, who cut Simien’s Dear White People (2014), as well as Haunted Mansion. “Edwin is very supportive and collaborative,” Georgiou tells ILM.com. “At the beginning, we were doing mostly set extensions, which is pretty straightforward. I think that he and Justin were impressed by the level of photorealism we were able to achieve, especially with the Mansion. Every shot of the Mansion has some CG, including the grounds around it. Another vendor, DNEG, was also doing some interior work, and we’d help create the views out the windows.”

Initially, Georgiou’s Sydney team worked only with ILM’s former Singapore studio, which being closer in time zones, shared the same schedule. “ILM has the best of the best,” Georgiou says. “Everyone was an amazing collaborator and shared their opinions. It was very open.” Principal photography had taken place in Georgia back in the United States, where ILM’s Andrew Roberts acted as onset visual effects supervisor. Georgiou and Munro also made a visit to Los Angeles to meet directly with the client, something Georgiou describes as essential to their continued partnership as the workload grew unexpectedly.

Reshoots would require further effects work involving an elaborate scene at the movie’s climax, where Ben (LaKeith Stanfield) confronts the villainous Hatbox Ghost (Jared Leto). “All of a sudden, we had more than twice as many shots as we started with,” Georgiou explains, “a CG human-like ghost character, and digi-doubles. It became an immense project, with over 1,000 shots. With a very short schedule, I think ILM knocked it out of the park. We had about 700 new shots, and Sydney became the hub for London, Vancouver, and San Francisco, as well as an additional vendor, Whiskytree. It became a global team. For my first real experience starting a project from the beginning at ILM, it was one of the best.

“When I first started on Stuart Little in 1998,” Georgiou continues, “one of the compositors who came in was R. Jay Williams, and he ended up being a senior compositor on Haunted Mansion [out of ILM San Francisco]. He had taught me so many things as a young roto artist, one of which was how to be nice to everybody. He always said hello and goodbye to everybody, one of the nicest, classiest people I’ve met in the industry, and I was able to finally tell him that on this project. It was so cool.”

During principal photography, a large portion of the Mansion was constructed as a physical set. “Mentally, psychologically, it was important to have a real mansion to shoot in,” Simien explains. “We could all get used to that physical space.” Other portions of the house incorporated bluescreen, including the sequence when Ben enters the ghost realm, a sort of alternate dimension within the Mansion where the hallways shift and rotate. This was amongst the work ILM received in the additional batch.

“It was quite interesting work,” Georgiou says. “Not only were we matching scans of the hallway reference that had been captured onset, but we were also matching the look to some of the previous work that DNEG had done. We then created animation for the rotations and how they would section off. The way they’d filmed onset with bluescreen was really well done, which made our work easier. The lighting was a challenge because there are candles and sconces on the wall, so you have these pools of light. The D.P. [Jeffrey Waldron] had very specific notes about how it should look. The chandeliers are swinging. Many puzzles to figure out, which is one of the best parts of visual effects. Overall, that sequence was one of the most successful, and it’s so cool that they used it in the poster.”

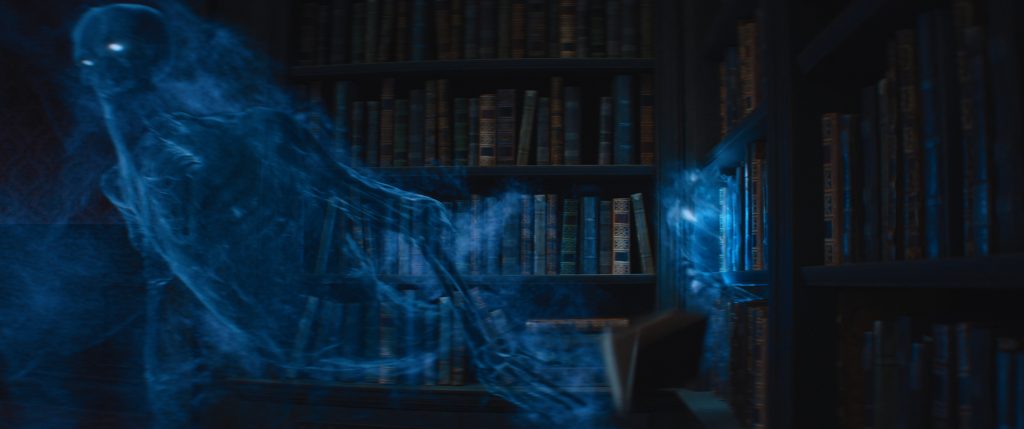

Of course, the appearance of 999 happy haunts would be the core element of Haunted Mansion’s visual effects. “Edwin Rivera used this term, ‘ectoplasmic effervescence’ for the ghosts, which has a Ghostbusters feel to it,” explains Georgiou. “It was fun to look through the history of cinema to find inspiration, but also figure out how we wanted to do things differently and create something that was fresh. Justin has such an incredible cinematic vocabulary. He’s looking at Kubrick and Hitchcock, and you can see that in how he’s framing shots. I felt like I was gaining plenty of knowledge.”

Another reference for Georgiou was Poltergeist (1982), one of ILM’s first client productions. “Poltergeist was very influential for me, especially when we were creating these skeletal ghosts that fly around. That was all connected to Poltergeist and the style they used for the ghost who comes right to camera. It feels really light-based but then there’s a skeleton face. Also, the way they use flares in Poltergeist was very influential for the last sequence of Haunted Mansion.”

A number of the prominently featured ghosts were performed by actors in costume and make-up. At times, ILM used digital doubles to replace them, each of which had to be modeled and textured. Others were entirely created with computer graphics, including the swarm of skeletal ghosts in the finale, which were original designs by the ILM Art Department. “The ghosts had a sort of x-ray feel to them,” says Georgiou. “It wasn’t a straightforward bone texture. We had to come up with how they glowed, both in day and night environments. They all had various types of clothing. Some had armor, or robes, or hoods. With all that comes a lot of creature work to get the costumes flowing properly. Then there are shots with hundreds and hundreds of them, as many as 600 or 700 at a time, which required crowd work. Our animation crew did hero shots, and they had the best time animating them. When they flank the Hatbox Ghost, they aren’t just standing there, but they’re chomping their teeth or doing little things with their hands. It’s subtle but it’s all there.”

The fan-favorite Hatbox Ghost is part of the lore of the Disney Parks attraction, and as the film’s chief villain, many different components went into his creation. “On the set, we had a great stuntperson named Colin Follenweider,” explains Simien. “We spent a lot of time discussing the physicality of the Hatbox Ghost, why he would walk a certain way. So he was in a suit on the set with a blue face. Then with Jared [Leto], we captured his voice. Then all of that goes into a blender at ILM where we have a team of animators fine-tuning every aspect of the performance. It’s a real amalgamation of a few different traditions.”

Georgiou explains that ILM’s fellow vendor, DNEG, had created the initial character model to produce an early batch of shots. “But it was never meant to be seen in bright lighting or anything like that,” he continues. “Every plate had the stunt actor. A human face with flesh and skin is very different from a more skeletal face. We had to figure out things like, how does the neck work? A skeletal neck wouldn’t fit around the wide neck of a human stunt performer. We were able to hide a lot of that behind the scarf he’s wearing. We had to figure out how the hat sat on his head. Onset, it was a little too low, but if it was too high, it looked more like a cowboy hat. There were a lot of challenges.

“Then there’s the clothing,” Georgiou continues. “In that final sequence, the earth is breaking apart, all of these ghosts are rising up. He has 999 ghosts, and he’s trying to get the last one so he can bring the ghost realm into the human realm. There’s a lot of shaking and wind. The stunt actor was on wires, and the clothing didn’t have much movement. In some shots, we kept the body and clothing and did a face and hat replacement. For around half of the shots we used a fully-CG Hatbox Ghost. The look development team worked very hard to match it to the actor onset. It’s pretty seamless.”

Georgiou explains how the character model was given new animation controls for his expanded performance. “We built that whole rig and made small controls for the wrinkles under the eyes, really small details in the face. It was really exciting. Our animation supervisor, Chris Marshall, helped us develop a lot of the facial performance for the Hatbox Ghost. I can’t wait to do another character like that.

“I kind of grew up doing shows like Garfield, Scooby-Doo, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe, and The Golden Compass where there are so many different types of visual effects,” Georgiou continues. “Haunted Mansion is very similar. We had ocean surfaces, a tsunami wave in an apartment along with its destruction, both interior and exterior. There were various effects elements, set extensions, digital doubles, crowd work, so many different kinds of shots. The Hatbox Ghost was a dream come true. Doing CG characters and placing them in live action was what I was raised on. It was a great opportunity to work on it. I’m so proud of our entire team. We have some incredible artists and I was the one who was lucky to be able to work with them.”

For Simien, the chance to tell a fantasy story laden with visual effects fulfilled his childhood dreams. “I grew up on effects-heavy films,” he says. “I’d lose myself in Star Wars, Star Trek, and X-Men. There wasn’t language for being a filmmaker when I was a kid. No one in my family talked about being a director. But what I would do is get home with the house to myself (I was a latch-key kid), put on a John Williams soundtrack, and pick up action figures and make them fight in these epic battles. I’d keep one eye closed to control the depth of field [laughs]!

“I didn’t know that I was directing,” Simien concludes. “I didn’t know that was a thing you could get paid for, but that’s what I did for fun. Having that big canvas is just part of my DNA. My first film was made for just over a million dollars, but it looks like it was made for more. To me, scale and cinematic spectacle is part of the fun of it. No matter what kind of story I’m telling, whether it’s something small and emotional or big and crazy like Haunted Mansion, I’m always going to push to see more in the world.”

Read about Skywalker Sound’s work on Haunted Mansion, including more from director Justin Simien.

_

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.