The ILM veteran worked on projects like Jurassic Park and The Mask, and helped create a special Halloween poster that inspired the moniker for ILM’s new podcast.

By Lucas O. Seastrom

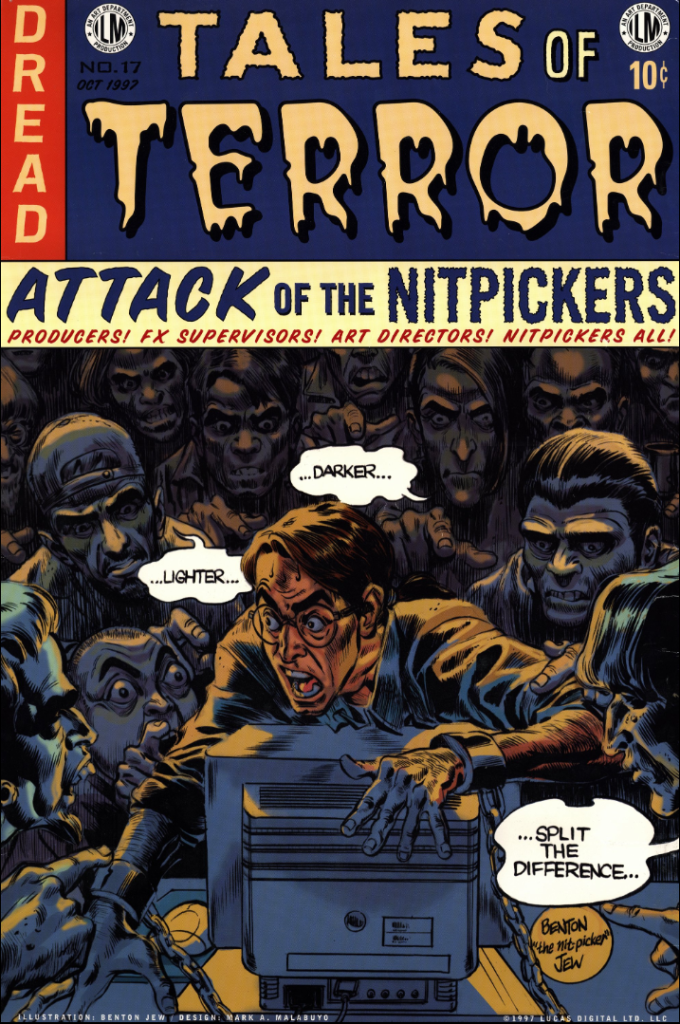

Listeners of the premiere episode of Lighter Darker: The ILM Podcast may be curious where the show found inspiration for its name.

27 years ago in 1997, Industrial Light & Magic was in the midst of the digital renaissance in visual effects, with projects as diverse as Men in Black, Contact, and Titanic being released that year, and others like Deep Impact (1998), Saving Private Ryan (1998), and Star Wars: The Phantom Menace (1999) readily underway. ILM’s then home at the Kerner facility in San Rafael, California was a bustling center of creativity across both digital and practical disciplines, and arguably the most exciting time of year came during Halloween season when hundreds of employees and their families gathered for an annual costume party.

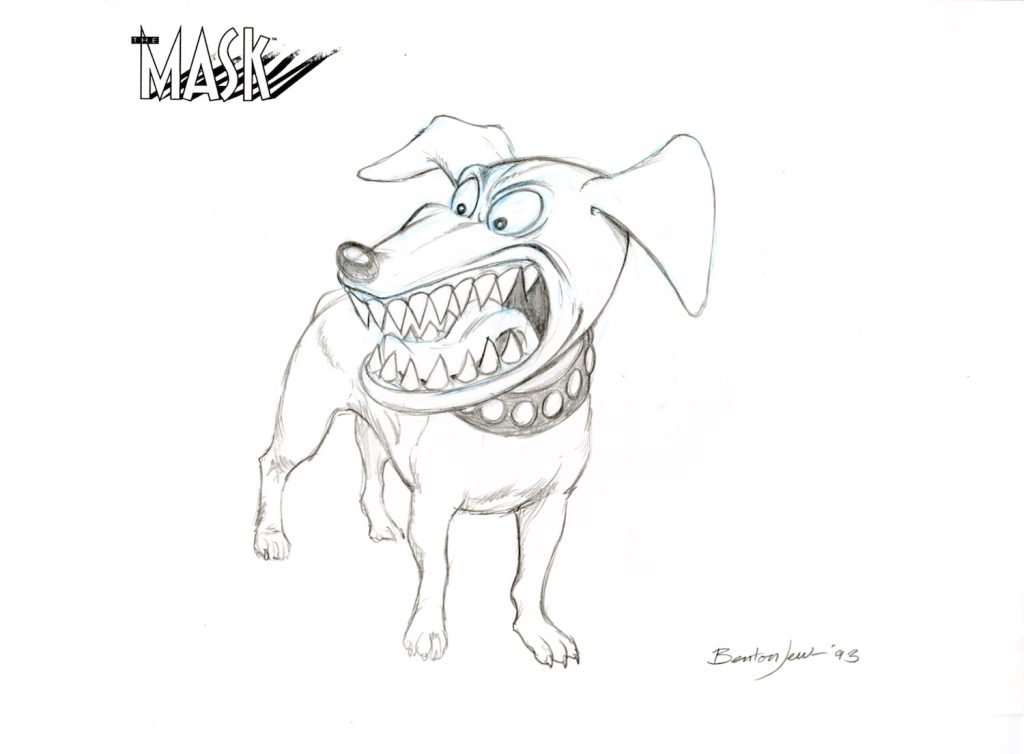

Benton Jew had been with the ILM Art Department since 1988, working as a storyboard and conceptual artist on everything from Memoirs of an Invisible Man (1992) to the fabled television commercial where basketball star Charles Barkley plays one-on-one with Godzilla. Later, his responsibilities grew as he became a visual effects art director on projects like The Mask (1994). But there was always time for side projects in between work for clients, and in 1997, Jew was asked to illustrate that year’s invitation and poster for the fabled ILM Halloween Party.

Designed by the late Mark Malabuyo, an in-house graphic designer at the time, the poster was envisioned in the style of the classic EC Comics of the mid-20th Century, known for their horror and science fiction stories. This “issue,” dated from October 1997, is entitled “Tales of Terror: Attack of the Nitpickers,” with the subtitle, “Producers! FX Supervisors! Art Directors! Nitpickers all!” Jew’s illustration below depicts a visual effects artist surrounded by figures caricatured in the horror style. He frightfully grasps his computer as the onlookers share their feedback about his work. “…Lighter…” one says, while someone else contrasts with “…Darker…” Yet another recommends, “…Split the difference…”

This tongue-in-cheek bit of satire about the collaborative process of visual effects would have inspired a chuckle from just about everyone at the company, and two of its word bubbles have now become the namesake of ILM’s new podcast. “I just wanted to capture that look of someone when a person comes by their workstation and points something out, or someone’s expression in dailies,” Benton Jew tells ILM.com. “It seemed like that kind of situation came up a lot in CG. Okay, no one can make a decision, let’s split the difference.

“Especially as an art director, I think I’d been seen as someone who would pick out little things,” Jew continues. “I’d be on The Mask or something, and would tell an artist, ‘Oh those icicles, they’re not quite right,’ or whatever it is. I’m sure that anybody who’s worked in CG can relate to that. People are always pointing and giving you backseat directions.”

Known within the department for his versatile and prolific output, Jew was also a lifelong comics fan, an attribute that earned him the Halloween Party assignment. “I was sort of the resident comic book geek,” he explains, “and obviously a Halloween piece would have an EC Comics theme to it. I tried to be in the spirit of artists like Jack Davis, Jack Kamen, and Graham Ingels. Mark Malabuyo was the graphic designer on it. He was a wonderful guy, so easy to work with. He was really jovial and friendly. We all miss him. He was set on making sure that the graphics had a fidelity to the old EC stuff. He made it as close as he could, with obviously some differences.”

Growing up, Jew had first aspired to be a comics artist. Then, as he puts it, “Star Wars happened.” The 1977 feature film launched the cinematic dreams of many younger viewers at the time, including Jew and his twin brother (who also became an illustrator). “We saw all the books on the making of Star Wars with Joe Johnston’s storyboards and Ralph McQuarrie’s drawings, and got hooked into amateur filmmaking. For people who grew up in that era when Star Wars came out, it really sparked a craze for people to want to be filmmakers.”

While studying at the Academy of Art in San Francisco with teachers like celebrated poster artist Drew Struzan, Jew was recruited into ILM’s ranks courtesy of storyboard artist Stan Fleming, who’d contributed to projects like Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984). Jew loved cinema, but never lost his passion for comics and illustration. “When I started working there, most people were from the car design world,” he explains. “They weren’t necessarily drawing figurative work. They were doing architectural or vehicle-driven stuff. As things became more creature-based in visual effects, being a general illustrator worked well for me. I can’t draw a vehicle to save my life.”

From the beginning, Jew worked as a storyboard artist, directly applying his knowledge of comics to another mode of visual storytelling. Among others, he’d eventually board for director George Lucas on The Phantom Menace. “With George, all of us would sit and do thumbnails with him. But I’ve worked with plenty of directors like that where I’ll sit with them and draw lots of tiny thumbnails really quickly, and then I’ll go back and flesh those boards out later. With George, we met with him twice a week for quick little meetings. He’d basically tell us the story, and we’d all draw out different ideas and he’d make suggestions. Then we’d have this huge stack of thumbnails, and we’d get them in correct order, and someone like me or Ed Natividad or Iain McCaig would make finished drawings from those.”

The digital renaissance led to a surge in projects requiring CG creature development, from early entries like The Abyss (1989) and Jurassic Park (1993), to even more ambitious projects like Dragonheart (1996) and The Mummy (1999). Jew had a front-row seat during this storied period that introduced new tools and tumultuous change. “My first real film was Ghostbusters 2,” he recalls, “and that was still done with foam and rubber and stuff like that. I got a pretty good idea of what that was like. I could see CG slowly coming into view. It was really a magical time and everything was changing by leaps and bounds.

“I would go down to ‘The Pit’ and watch Spaz [Steve Williams] creating those dinosaurs that he would later show to Spielberg and company,” Jew continues. “It was so weird when Jurassic Park was being made because you had to sit on this and not tell anybody, and you knew it was going to change the world. As the technology kept improving, it wasn’t replacing the artists and filmmakers; it was helping them. It’s about giving them the tools to make something that they couldn’t make with traditional means…. John [Knoll] would come by and ask us what we wanted to see in Photoshop. He meant for it to be a tool for us, not a replacement. Our pallet was growing larger.”

Departing ILM in 2001 after 13 years with the company, Jew headed for Los Angeles where he continues to work on feature films as a storyboard and concept artist. He’s also self-published comic books of his own, as well as contributed to comics for Marvel, among others. Jew still gets questions about the memorable “Tales of Terror” poster (and remains adamant that the terrified artist clutching his machine is not based on anyone in particular). Looking back on his ILM days, Jew values the artistic lessons granted him by the experience of working on so many different assignments.

“Just the idea of having to do a lot of stuff very quickly impacts how you draw,” he concludes. “You learn to do more shortcuts, what to leave in, what to take out, and things like that. Early on, I didn’t do a lot of paintings. Most of my stuff was black and white, but I learned to do more color stuff when they asked me to do it. The volume, speed, and needs always change, so you just stay flexible. As an artist or an art director, the most important thing is not your eyes or your hands, but your ears. To understand what the director or effects supervisor wants, you need to develop your ear more than anything. It’s learning what they want and how to do it correctly. It may not be your own taste, but you need to be able to talk to them and know where they’re trying to go with it.”

–

Lucas O. Seastrom is a writer and historian at Lucasfilm.