ILM artists Ian Milham and Shannon Thomas take us behind the scenes of in the second of a two-part story about the 2024 Summer Olympics in Paris and 2026 Winter Olympics in Milan.

By Lucas O. Seastrom

Read Part 1 of this story here on ILM.com.

After ILM successfully created a landmark mobile deployment of its StageCraft virtual production system for the 2024 Paris Olympics coverage, it was only natural to up the ante for the next round. As a continuing partnership with NBC, the 2026 Milan Cortina Winter Olympics in Italy presented a batch of creative challenges that introduced a new level of dynamic presentation to ILM’s imagery. This included everything from shooting with a real ice rink in the foreground to simulating continuous motion on the volume’s LED wall.

“It was like the band got back together with this one,” notes virtual art department (VAD) supervisor Shannon Thomas. “It was the same crew on the client side. This time the process was less educational in terms of how we interacted with the client or explained how best to use the LED volume. They now understood how it would work, so this was about executing the same kind of creative process but with all new sets. Right from the start, we were able to get down to the specifics of what they wanted to achieve.”

Milan Cortina: The Brief

As with Paris, ILM’s task was to create a series of LED volume loads that acted as backdrops for athletes from the United States Olympic team. Footage of the athletes striking poses and performing actions in each setting would be utilized for any number of promotional needs before and during the Games. NBC brought six ideas for locations to the ILM team, and together they brought new layers of complexity to the job of realizing each of them.

A majority of the settings featured natural, snowy landscapes of the Italian Dolomites, including a mountain top, a frozen pond in a small valley, a ski lodge that looks out across an alpine vista, and a “moving” chairlift up a mountainside. Additionally, two Milan locations incorporated local landmarks, the Piazza del Duomo with its namesake cathedral and lustrous Galleria, and the interior of Teatro alla Scala, Milan’s 18th century opera house, which included an ice rink on the stage.

Initial challenges included the need to accommodate a massive scale of mountain landscapes within the visible scope of an LED volume wall. There was also the active motion of the athletes, a key difference from Paris. Ice skaters and hockey players would actually be moving across the small ice rinks built as practical sets in front of the volume wall. Not only did ILM’s technology need to coexist alongside the ice, but the camera needed to track effectively with the talent’s movements while also maintaining the appropriate sense of depth with the background.

As with Paris, the stylistic brief was to create a sense of hyperrealism, with accentuated lighting and staging. But the natural settings required a new level of realism to feel believable, compared to the Paris sets which were more idealistic. ILM artist Giles Hancock joined the NBC team on a location visit to Italy in early 2025. “Giles captured a ton of photo and video reference plus LIDAR scans of the actual locations,” says ILM virtual production supervisor Ian Milham. “We could then use that as the basis for the content that we made for the wall. That involved someone staging a camera tripod in different spaces, and even riding a chairlift, as well as some data from a helicopter flight.”

Setting the Scene

Both ILM’s past experience and its established relationship with NBC empowered the team’s ability to begin planning from a very early stage. “We did quite a bit of animated previsualization,” says Milham. “The athletes were actually performing their sport, and there were concerns about space and safety, of course, but we also needed to make sure that we could follow and track them in a way that did justice to their real movements.”

Understanding the parameters for the shoot, what Milham calls “the edges of what’s possible,” ensures that the ILM team can deliver everything that could potentially be needed on the day. The client is likewise empowered to envision whatever they can within those set parameters, as well as plan the practical foreground elements. And, of course, there are times when both the client and ILM work to push the established boundaries and see how much more they can do.

For the digital backgrounds, individual settings required their own distinct finessing, in particular the Piazza del Duomo. “Lead hard surface modeler Masa Narita modeled all of the buildings for that entire city square from Giles’ scans, and texture artist Maria Cifuentes textured that entire set as it looked in real life in Milan,” Thomas explains, “and I then lit the real time set based on our digital sky select, and incorporated where the practical ice rink would have to live inside the volume. I then had the new challenge of determining where you would have to physically be, if you were in front of a camera in the real Piazza square, in order to also see the top of the Duomo’s tallest spire. We quickly realized that even with a wide focal length we needed to pivot in order to ensure we could see the whole building.”

Because the Duomo’s cathedral is over 600 years old and such an important national landmark, it was necessary to make sure that the building’s recognizable shape could be seen in its entirety. This resulted in a slight increase in the size of the LED volume from what we used for Paris. ILM’s R&D engineers and technical teams designed a virtual LED volume tool which allowed Thomas and his team to instantly add more rows or columns of panels, all adjustable in real time to ensure that the physical LED volume built on the day would capture the full height and beauty of the Duomo.

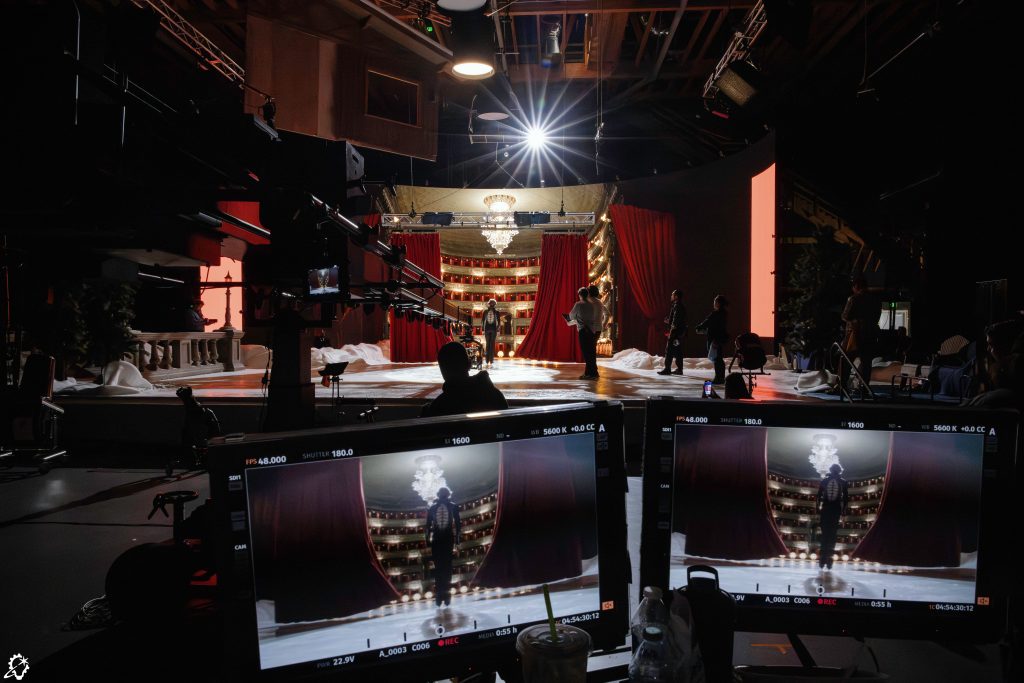

For the opera house interior, Hancock’s photogrammetry data provided a useful foundation. Narita and Cifuentes again created a photoreal CG asset for the space, which Thomas and lead virtual production technical director Rey Reynolds then staged in appropriately gold-tinged warm light, including the illustrious digital chandelier. On the set, practical red curtains, some 30 feet tall, augmented the background. “They could open them like real stage curtains in camera to reveal our LED content,” Thomas explains, “so that it felt like you were on a real stage, and behind it was the virtual opera house, an ice skater on real ice, fake snow, and real movie lighting. It was so cool. It looked like magic. It’s a great example of using the tool exactly how it should be used, not forcing it.”

The ice itself was roughly 20 feet long by some 40 feet wide. A refrigeration unit was specially designed into the space. A fair amount of research and planning was involved in determining the necessary space required for the athletes to get up to speed and perform. “Hollywood is crazy in terms of what they can do onsite,” says Milham. “You have to keep the room cold, of course. It’s all internally cooled like a hockey arena. It’s logistically difficult in terms of how things are built. You have to install the wall first, then build the rink, then leave the rink for a couple days so it freezes.” Practical snow was also used on multiple sets, which, as Milham notes, “adds the magic of it falling onto people or the sense of depth as they travel through it.”

The most elaborate practical foreground set was for the patio deck at the ski lodge, which included an actual fire pit, furniture, stringlights, a surrounding fenceline, and even a small tree that needed to match with ILM’s CG counterparts. The effects team initially decided to create the background as a standard 2D matte element, but when the client planned more dynamic camera movements for the scene, ILM pivoted to an elaborate 3D environment. Senior VAD artist Nate Prop led its creation, which allowed the team to make specific changes to the mountain view as needed. And Thomas notes, “[VAD supervisor] Christy Page even added little cars driving in the town, so you could actually see little headlights moving out there. The lights flicker in the town as well.

“There’s enough of the practical elements to tie you into the background,” Thomas continues. “The way they shot it works really well with the real fire pit and cabin structure, fence, trees, etc. Though if you move the camera just a couple feet to the left or right, you see all of the structural wood boards of the practical set build, like it’s a high school play. But in-camera, the shot works, it looks like they’re really there.” Actor Scarlett Johansson and Olympian Lindsay Vonn would be among those to shoot on the lodge set.

Adjusting the Frame Rate

A significant technical change for the Winter Olympics production was to capture footage at 48 frames per second (fps). The additional frame rate would allow the client to modify the imagery to varying speeds as needed, and in particular with athletes zipping about on the ice.

“The difficulty with that is when shooting with a StageCraft LED screen, you need very exact synchronization between your camera, the content, and the wall,” Milham explains. “So with a higher frame rate, that’s orders of magnitude harder because you have to sync to 1/48th of a second instead of 1/24th of a second. Your content needs to do all of its transformation in half the time and everything else with it.”

Without the proper synchronization, a number of issues can arise, including a flicker effect visible on the LED volume, as well as on the foreground subjects and elements because the wall acts as both a background and a light source. On the previous Summer Olympics production, the cameras ran at 48fps but the wall content projected at 24fps, which meant there were limitations to how the final footage could be adjusted after the fact. By request of NBC, Milan Cortina became ILM’s first all-48fps volume shoot.

ILM imaging supervisor J Schulte and principal engineer and architect Nick Rasmussen coordinated weeks of rigorous testing for the chosen Alexa 35 camera system. The results provided much greater flexibility, especially with the demands of the Winter Olympics settings in mind. “It’s important to have if you’re really flying the camera around, like a push-in or a big crane move,” says Milham, “and we did some gigantic crane moves on this project.”

As they had with the Paris shoot, ILM ran three separate renderers to allow for quick changes between scenes. But in this case, two projected to the LED wall at 48fps, while the third projected at 24fps for set-ups that involved audio capture. Interviews and related scenes with dialogue would not require dramatic adjustments in speed.

Just Like the Old Days

Perhaps the most distinctive of the volume loads for the Winter Olympics involved a chairlift that appeared to be moving through the Dolomites. The scene was initially planned as a standard interview set-up, with three locked-off cameras positioned to cover two or three subjects in the chairlift. This would require a moving background on the LED wall that ran for an extended time.

“NBC didn’t want to cut, because they might intercut the footage with other material, and then cut back to it,” Thomas recalls. “They wanted to just roll and let the people talk and get comfortable. They might only use a piece of it three or four minutes in. That means you need to run a lot of footage, and it has to loop at about eight-minute intervals. When you think of a Star Wars movie or something like that, you might have around 2,000 shots that a team of hundreds executes over months or years. Most of those shots are a few seconds to maybe 20 seconds long. We had to render eight minutes of a straight looping footage in a fraction of the time with one or two artists. It was a ton of work and data to maintain.”

Nate Propp again took the lead, visualizing a system that placed two opposite rows of mountain landscape moving in parallel on either side of the talent, not unlike a conveyor belt. “It didn’t matter if the mountains weren’t the exact layout of the Dolomites. We used all of Giles’ scans to piece together a long track of digital mountains that felt like the Dolomites versus having this specific mountain peak perfectly line up to that one. Our earlier Paris Olympics set work aided us here, so as long as we captured the essence of the Dolomites, it worked,” Thomas notes. “The conversation with the talent was the real focus. So Nate laid it out and duplicated a mountain landscape like railroad tracks, that could loop, basically to infinity. We could then place the ski lift in with the camera and ride this imaginary track for as long as they wanted.”

It required a great deal of experimenting to then determine the best means to render such a lengthy scene at 4K without overloading the machines. Additionally, there were concerns about maintaining consistent lighting. “What can break that set-up is not necessarily the background, but rather the feeling that the people aren’t actually moving through it,” Milham says, “and that’s usually because the lighting on them isn’t changing enough.” Coordination with the on-set, practical lighting team allowed them to find the appropriate balance. The volume itself can be equipped to synchronize directly with a traditional lighting grid.

The chairlift set-up became even more elaborate when it was decided to actually move the formerly stationary cameras during the scene. This required ILM to create additional pieces of the landscape on the fly to fill in previously unseen gaps. “It’s all our system and our artists,” Milham notes, “so we’re able to do that at the last minute.” That included associate virtual production supervisor Brad Watkins, who partnered with Milham in directing the team on the stage.

The final results, as Thomas points out with a smile, “are the same as Alfred Hitchcock’s background of Mount Rushmore in North by Northwest. It’s the same magic trick they pulled off in 1959. But now you can move the camera and get parallax.”

The Art of Collaboration

During pre-production, the ILM crew demonstrated their various plans for the set-ups to NBC. They showed the chairlift scene last. “We had the initial presentation that showed what you’d actually see from each camera,” Thomas explains, “and then we showed what the footage was actually doing on the site, this incline into infinity. Ian is pitching it and explaining what can be accomplished. And one of the folks from NBC turns to his colleagues and says, ‘Guys, this is it! This is going to work!’ We were so happy that they liked it, in particular, because we knew how important this specific set was for their vision. “I’ve learned through the years that, with any client, you want to really listen in to what is important to them, and then hit that specific note to reinforce that you are a team working together to achieve a shared goal, this is what builds confidence with your client.”

Throughout these Olympics collaborations, the key for ILM has been an equal mix of flexibility and adaptability to meet the client’s needs. The continuous, energetic shooting style only further demonstrated the versatility of ILM Stagecraft, and likewise ILM’s ability to meet the needs of any client.

“There are ‘unlocks’ here in terms of what is possible with last-minute scenarios, or in-demand talent, in terms of pulling off an ambition that otherwise would not be possible,” Milham concludes. “It doesn’t have to be Star Wars. You can use this technology to make sets appear very, very fast, and to take advantage of a small window of time with talent, all without limitations, and we can do it anywhere.”

—

Lucas O. Seastrom is the editor of ILM.com and Skysound.com, as well as a contributing writer and historian for Lucasfilm.