The visual effects supervisor discusses ILM’s contributions to director Ryan Coogler’s supernatural sensation, which is nominated for “Outstanding Supporting Visual Effects in a Photoreal Feature” at the VES Awards.

By Jay Stobie

Helmed by writer/director Ryan Coogler, Warner Bros.’ Sinners (2025) defies the boundaries of traditional genres, telling the story of Elijah “Smoke” and Elias “Stack” Moore (both played by Michael B. Jordan) as they return home to establish their own juke joint. Forced to deal with the cruel inequalities of 1930s Mississippi and a ravenous vampire named Remmick (Jack O’Connell), the twin brothers’ exploits are paired with an exhilarating blues soundtrack and live performances. ILM visual effects supervisor Nick Marshall (The Last of Us [2023], Dune: Part Two [2024]) joined ILM.com to outline Industrial Light & Magic’s visual effects contributions to the film, which included a near-fatal encounter with a symbolic rattlesnake and a train’s entrance into a bustling station.

A Bewildering Briefing

“As the ILM visual effects supervisor on the film, I looked after a small body of work, by ILM’s standards, as we handled just under 100 shots covering two different sequences,” Marshall explains to ILM.com. ILM’s work on Sinners took place at ILM’s Vancouver studio, and Marshall recounts how the first story overview he received left him slightly perplexed.

“Early on, people were quite tight-lipped over what this movie was. We had an excellent collaboration with the filmmakers in terms of the technical understanding of the visual effects we were going to do, but the bigger picture was kept close to the chest. Sinners was outlined to us as a period movie with a gangster element to it, and racial segregation was also an important plot point. At the same time, it’s got a big supernatural element, and Michael B. Jordan is playing twins. And, as all of this is going on, the heart of the movie is about blues music.

“When we got this initial brief, we thought it was a bit bizarre but sounded very interesting,” Marshall continues. “There were so many elements to the story that it got to the point where I asked the client if it was going to be a comedy [laughs]. They said, ‘No, it’s actually a serious horror movie.’ As we progressed with our work, the plot unfolded, and we understood a lot more. Even though we didn’t necessarily know exactly what the movie was about until a long way into production, there was such a passion from everyone going into it. We could tell we were working on a pretty special project with a clear vision behind it.”

Rumble with a Rattlesnake

The first ILM sequence to appear in the film centered upon the twins discovering a rattlesnake concealed in their truck bed, leading Smoke to stab the snake with a knife and toss its bleeding body onto the ground. “Ryan described this moment as foreshadowing, as it echoes the moment when Smoke has a standoff with Cornbread [Omar Benson Miller] outside of the juke joint later in the movie. The snake scene is the first time you get a sense that there’s something off and maybe even supernatural about this world that they’re in, so we went deep into trying to give that meaning. The idea of familiars foreshadowing bad events repeats often in Sinners – there are ravens, crows, and vultures which appear throughout the film and establish that there’s a tension building.”

In terms of the snake itself, the ILM team had plenty of information to base their visual effects on, as Marshall notes, “Ryan Coogler is an avid snake collector and knows a lot about them, so we were going to have to do justice to the real thing. Ryan told us how snakes that are shedding their skin get more aggressive – they’re in a heightened state because they’re weakened by it – and that they get a layer of skin that creates a cloudy-eyed look, which ties in nicely to the tapetum lucidum effect that the vampires’ eyes have in Sinners. Production shot a real timber rattlesnake in the back of the truckbed for us as reference, and the one place where we deliberately made a creative change which differed from the real snake, was to give the eyes that shedding-skin appearance. [Animation lead] Agata Matuszak sat down for weeks looking through internet references to find every perfect snake attack shot that she could locate – snakes striking into the camera, at a mouse, or toward balloons and seeing how quickly they move. She became a brilliant source on snake locomotion.”

The scope of ILM’s contributions to the snake sequence changed over time as the edit continued to evolve, with Marshall declaring, “The reference served us well as far as providing a snake to visually match to, but we were originally only supposed to do a single shot of the snake. They were going to capture the snake being uncovered, waking up, and all of that practically, and we would take over when the snake had to be stabbed. However, they couldn’t get a performance out of the real snake on the day of – it was happily toodling around in the truck bed – so we took over and delivered around 10 shots of the snake. Not all of those shots made it into the movie, because they were still experimenting with ideas for what actions they wanted from the snake.”

The ‘Pool Noodle’ Process

ILM’s approach to the snake sequence needed to factor in the reality that Smoke would be interacting directly with the knife and the animal itself. Marshall relays, “For lighting purposes, we had to make sure that the knife was blocked accurately when Smoke brought it down over the top of the snake’s head. We did a basic digital double version of Smoke and reprojected some of the plate back onto that so – if you ever saw anything in a reflection – it had the correct texture of his hands and suit. We kept the knife as practical as we could but eventually took it over because the knife very visibly enters the snake’s head. We reconstructed the knife prop and used that for the reflections of our CG assets and blood interaction.”

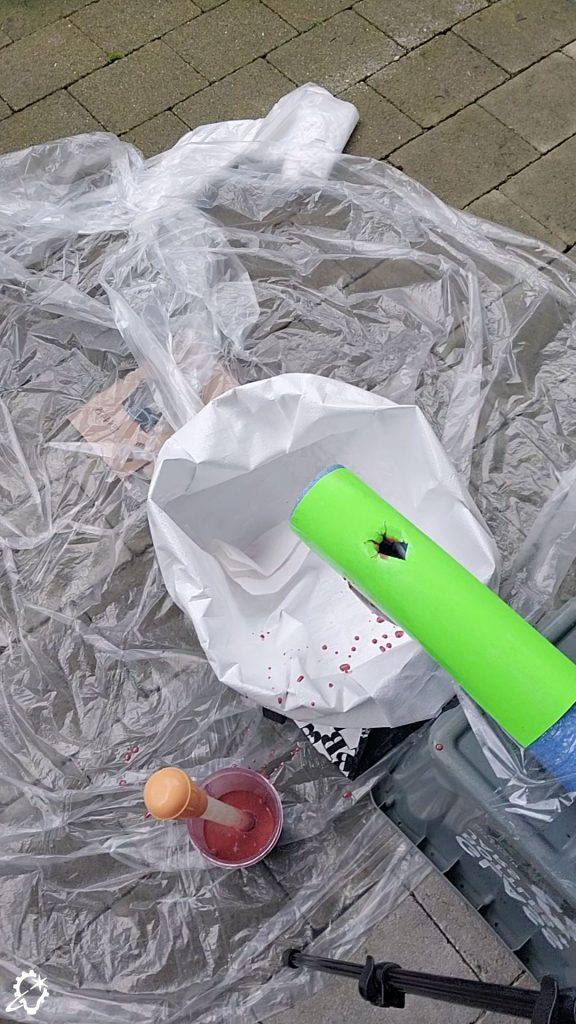

Turning to the blood that pours from the rattlesnake, Marshall says, “Our effects team did amazing blood simulations for the blood spatter, and when you see all of the interaction with the knife. When the knife pins the snake’s head, you get blood leaking out from underneath and spreading across the truck bed, as well. Our effects team totally nailed it. The lone aspect we came in to touch up was the blood pumping out of its neck wound when it’s tossed into the long grass. You get a few shots of it writhing around as it’s dying. That ended up being a combination – the effects simulations for the blood spatter as it hits the ground, and we also did a practical blood element shoot at the last minute to sell the sense of the viscous blood pooling on the surface and trickling down the sides.”

This impromptu ILM shoot involved an unexpected tool, as Marshall shares, “We shot it in my backgarden, where it was a construction using a pool noodle that had been hacked apart to represent the snake. We rigged up blood packs to pump blood out of an artificial wound that we had cut into the pool noodle. Our comp team, under the supervision of Okan Ataman, made the best of it and pulled it together using the most successful elements from our effects simulation and our practical shoot. That combination got us over the line, and the client was extremely happy with it.”

Locomotive Magic

The second sequence ILM presided over focused on a train arriving at a Mississippi station. “We did a lot of photorealistic reconstructions of the Clarksdale train station,” Marshall begins. “When we started discussing it, production was going to have a real locomotive come into the station. We were just going to do environment extensions. As it turned out, they struggled to make it work with the timing and location, so we took over the train component too. That became a big deal for us, because we had assumed the practical train would block a lot of our environment throughout the sequence.

“The train wound up being full CG itself, and we were shooting directly into the green screen – which is daunting with visual effects because it can telegraph itself,” Marshall divulges. “Fortunately, production assisted us by building the green screen to the exact height of the train so we’d get correct shadows. Since the train was green as well – which is true to the period – a small amount of green spill contaminating the environment wasn’t necessarily the worst thing. Normally, that would be bad for us, but here it served as a fantastic reference for where the top of the train should sit. It gave us the correct shadow and lighting for what came over the top of the train once we put the train in to replace the green screen. This allowed us to have wonderful light interaction with the characters.”

Real-world references are essential to visual effects work, particularly when dealing with such a distinct time period. “We had tremendous art department concepts that production designer Hannah Beachler put together in collaboration with our production visual effects supervisor, Michael Ralla. Those served as the basis for the broader design of the streets, the kind of signage we would get, and other specifics like that. We supplemented them with our own research for period details about the streetlighting and electronics you’d expect around the trains. At that point, they were going through the transition from steam locomotives to electricity. [Environment supervisor] Anton Borisov pored over old photographs to see what Clarksdale really looked like in the 1930s. We went into an extensive research period to figure out the mechanisms that were active on the rail at that point and how the carriages looked, right down to the numbers you see on the side,” Marshall reveals.

The film’s setting had an impact on ILM’s responsibilities, as Marshall elaborates, “In collaboration with the client, we ensured there was a sense of racial segregation to the environment, so you could see a clear delineation between the side of the tracks reserved for whites and the side that was designated for Black people. It was a key plot point for the movie, and we wanted to do justice to it. Beyond that, our goal was to make everything look as photoreal as possible. The client wanted our work to blend seamlessly so no one would notice that they occasionally relied heavily on visual effects. In certain cases, the visual effects took over the majority of the frame, but it always had to disappear and be completely invisible.”

Buildings, Automobiles, and Bystanders

Although production built a full-scale physical train station to be used on the set, ILM nevertheless offered support in post-production. “We did a bit of repair work on the train station itself, which they did shoot practically. Production put significant time and effort into the building with the understanding we’d handle the majority of the environment extensions. There were a few places where tiles were missing and shingles fell off, and we did the train tracks that the train rolls in on,” Marshall adds.

Research and reference entered play once again when it came time to outfit the environment with traffic and pedestrians. “As far as the cars you see, we sought to add life to the background,” Marshall remarks. “We didn’t want the set extension to feel static, so we researched Ford automobiles from around that time. Cars were fairly limited in their color palette in that era, as you’d tend to mostly have black paint, so we didn’t have to do too much variance in colors for the automobiles.

“Our CG supervisor, Anthony Zwartouw, gathered reference photography and basic assets, then we pieced together the design of the vehicles,” Marshall continues. “Then, we went about building them, and our animation team did a phenomenal job of making the cars seem as if they were trundling over uneven ground. Our compositing team led by Michael Ranalletta, was outstanding too – they went in and fleshed out the background with 2D sprites of people. Production shot a ton of 2D elements of people milling around, holding luggage, talking, and walking about. We used those to populate the backgrounds and achieve the busy, lived-in environment that they wanted.”

“Invisible” Involvement

Marshall indicates that Sinners was shot on large format film, and the shots which ILM worked on were shot on System 65, “a super-wide format that’s been used on movies like The Hateful Eight [2015]. Since film is shot infrequently these days, we had to rebuild and relearn certain parts of the pipeline to be able to cope with that. What might’ve been simple requests in a digital workflow, such as additional takes of a particular shot or extending a frame range, became quite complex and expensive. They had to order those frames to be re-scanned, and there aren’t many people who do it anymore. Certain points were tricky, as it can be difficult to naturally ingest physical film into our digital pipelines. [Color scientist] Matthias Scharfenberg did remarkable work to give us a color process that allowed us to progress with the movie.”

“Along with that, there’s a physical quality to the way Sinners was shot that we needed to emulate too. [Director of photography] Autumn Durald Arkapaw shoots on deliberately de-tuned lenses, and she’ll send them off to have little abnormalities and subtle effects appear in the lenses because she wanted them to have character. Where a lens might customarily be uniform across its surface, hers had slight shape changes. Our compositing team with [comp supervisor] Okan Ataman and [comp lead] Michael Ranalletta did some significant lens profiling work, because things would warp in strange ways and go in and out of focus in places you wouldn’t expect.”

“[Digital artist] Florian Sanchez literally sat for over a month just profiling our lenses to see if we could set the tooling internally, which took a perfect CG render and added those subtle changes. When we’d get our perfect CG renders to come out, we then applied all these effects that were – in many cases – degrading the actual image. However, that made it feel exactly like it was this real film format that could’ve been used to shoot this movie 40 years ago. We’d add tons of grain and noise over the top, plus small dust hits here and there. We wanted our work to not look digital in what was otherwise a sort of analog movie, so we had to reapply those details to our CG.”

Other less-obvious contributions which ILM made to their assigned sequences tied in to the director of photography’s preferred approach to lighting shots, as Marshall conveys, “Autumn shoots with a lot of negative fill – she’ll put up huge black flags and canopies just out of camera to block light and create shaping on the characters’ faces. It’s a more natural way of working, but it meant that the 360-degree high-dynamic range images we’d usually use to light our scenes had massive black canopies in them. When they filmed at the station, they didn’t have a representation of the train when they shot it for real, so when we put the train in, we started getting reflections of those canopies. [CG supervisor] Anthony Zwartouw made sure the lighting across the sequence was solid. Anthony helped us come up with a good system for lighting these shots in a way that let us do a big pass at taking that stuff out digitally and projecting the results onto a low resolution LiDAR scan of the location, so we had a clean digital set which we could use to light our assets.”

Motion Picture Partners

Marshall’s effusive praise for his ILM team extends to the client-side filmmakers, as the visual effects supervisor beams, “My direct contacts on Sinners were Michael Ralla and visual effects producer James Alexander. Not far into our work, I understood that they had a super collaborative team who valued our input. Michael made regular efforts to stop us from referring to ourselves as a vendor. Michael said, ‘You aren’t a vendor, you’re a partner in this process, so let’s scrap that word from the playbook right now.’ To their credit, they walked the walk. When they were out on set, they’d call us to consult on critical decisions. ‘We’ve hit this problem, so do you want us to put a green screen here or there?’ They wouldn’t be able to do both because of budget or time constraints, but they’d involve us in those conversations.”

These discussions benefited ILM’s workflow immensely, as Marshall asserts, “We weren’t waiting to receive plates and unaware of what we’d be getting to work with. We were incorporated into the decision-making and could plan what we had to do.” Marshall attributes the collaborative spirit that permeated the production’s departments to the director, observing, “Ryan’s a collaborative filmmaker, and he’s always present – he’s engaged and drives the film. There was so much respect between the departments, and we each tried to resolve issues you may not even think about.”

Marshall credits the members of his ILM production team for keeping them on schedule and adapting to editorial needs. “Ryan was making adjustments to the timing of the cut as it’s the first time Smoke and Stack separate from each other in the movie, so we built our process to be flexible and allow Ryan the freedom in the edit room.. Our producer Alan Cummins, [project manager] Kaisha Williams, and the production team worked tirelessly to guarantee that we were left with enough time to fit in everything that we needed to do, which enabled the filmmakers to continue making those last-minute changes.”

Valuing Visual Effects

Marshall emphasizes Ryan Coogler’s appreciation for visual effects, professing, “In recent years, you’ve seen a continued trend toward pretending there’s no visual effects involvement in films. Ryan bucks that trend. Ryan shot as much as he could for real on Sinners, but he’s a huge proponent for visual effects being a part of the process. For Ryan, visual effects are absolutely indispensable to the team. It’s nice when a director goes out of their way to give credit to the visual effects companies as another department that brings their vision to life. We never felt as if our contributions were being downplayed.”

Speaking to the role of visual effects in filmmaking as a whole, Marshall says, “All visual effects artists and supervisors want to do is deliver the best work and help people tell interesting stories. Keeping visual effects as part of the conversation is something to be championed, and Sinners definitely did it right. The more that those conversations happen out in the open, the better. When we wrapped our last shot, Ryan sent us a video to thank the team and recognize us for our work. Sinners was a special show to be on in that way.”

The thoughtfulness displayed by Coogler and the entire Sinners crew made the experience of working on the project an exceptional one for Marshall, who concludes by offering his perspective on the completed film, affirming, “Ultimately, there’s so much symbolism in Sinners that I hope people can keep digging back into it and watch the movie again and again. There are so many intriguing parallels and nods to later scenes scattered throughout, and a great deal of history and culture that are crucial to the movie. So much thought went into every frame, and every shot has a purpose and a meaning. Because of that, and because ILM was brought into the loop to aid in making it that way, I hope Sinners will be one of those movies that stands the test of time. In 10 to 20 years, people can rewatch it and say, ‘I’ve never caught that moment even though I’ve already seen it five times. That’s a really nice detail!’”

Watch an ILM exclusive deleted scene from Sinners:

–

Jay Stobie (he/him) is a writer, author, and consultant who has contributed articles to ILM.com, Skysound.com, Star Wars Insider, StarWars.com, Star Trek Explorer, Star Trek Magazine, and StarTrek.com. Jay loves sci-fi, fantasy, and film, and you can learn more about him by visiting JayStobie.com or finding him on Twitter, Instagram, and other social media platforms at @StobiesGalaxy.