The ILM visual effects supervisor reflects on ILM’s contributions to the riveting film inspired by a compelling real-life story.

By Jay Stobie

Inspired by the events of the 2018 Camp Fire in Paradise, California, and based on Lizzie Johnson’s 2021 book “Paradise: One Town’s Struggle to Survive an American Wildfire,” The Lost Bus (2025) follows Kevin McKay (Matthew McConaughey) and Mary Ludwig (America Ferrera) as they attempt to shepherd 22 children to safety aboard a school bus during a chaotic evacuation. Directed by Paul Greengrass (The Bourne Ultimatum [2007], Captain Phillips [2013]), who co-wrote the screenplay with Brad Ingelsby, the film puts the audience in the front seat on a harrowing ride through the awful inferno.

Industrial Light & Magic’s Dave Zaretti (WandaVision [2021], Willow [2022-2023], The Acolyte [2024]) generously took time to sit down with ILM.com and discuss his role as the project’s ILM visual effects supervisor. In a wide-ranging conversation, Zaretti touches on studying real-world references, crafting intricate assets and environments, paying respect to those who endured the tragic events depicted in The Lost Bus, and much more, detailing every level of ILM’s extensive contributions to the captivating film.

Real-world References

As the ILM visual effects supervisor, Zaretti operated out of the London studio and oversaw the company’s work on the project. “I think ILM had the lion’s share of the visual effects work for the second part of the film,” Zaretti tells ILM.com. “I supervised all of the London work, and we had work from ILM’s Mumbai studio that [ILM associate visual effects supervisor] Steve Hardy supervised. My daily role was to keep an eye on the overall vision of the show and check in with Charlie Noble, the client-side visual effects supervisor.”

Noble supplied ILM with what Zaretti describes as a nearly two-hour-long “megaclip” of reference material, which helped ILM ground their visual effects shots in realism. “I’ve never had so much reference on a show,” Zaretti emphasizes, “because this event occurred in 2018, and everyone had phones and cameras. It was a very filmed event. A pickup unit also went to Paradise and filmed loads of additional footage of the actual place itself. In terms of the environment and road layouts, we spent a long time on Google Maps ensuring we got all of the turns in the road correctly.”

ILM broke up the reference megaclip into separate asset types. “We had shots within the smoke cloud, shots outside of the smoke cloud, big fires, small fires, brush fires, trees burning, houses burning, and cars burning,” Zaretti recalls. “There were fire tornadoes; I didn’t even know that was a thing! We were spoiled with references to the point where the references began to contradict each other because there’d be wind blowing in two different directions in the same piece of footage. Those contradictions actually helped us in certain scenarios. For example, during the escape sequence when the bus is winding down this thin road, there are points where we had flames licking at it from both directions to portray the danger that they were in. So, having a real reference to back up your visual effects often helps.”

Assembling Assets

The abundant reference footage proved incredibly useful; although, its varied nature also meant ILM needed to build a wealth of digital assets to fully represent the range of material. “We had about seven types of fire assets,” Zaretti says of the meticulous process. “You’d think fire would count as one thing, but no, we had small, medium, and large fires. We had traveling fire that was needed to show the spread of fire through the grass. There were several types of smoke because vegetation has a lighter smoke, while houses and cars have a darker, roiling, inky smoke.” Surprisingly, minute embers seen amidst the chaos are burning or smouldering pine cones, reflecting the heavy debris encountered throughout the 2018 fire.

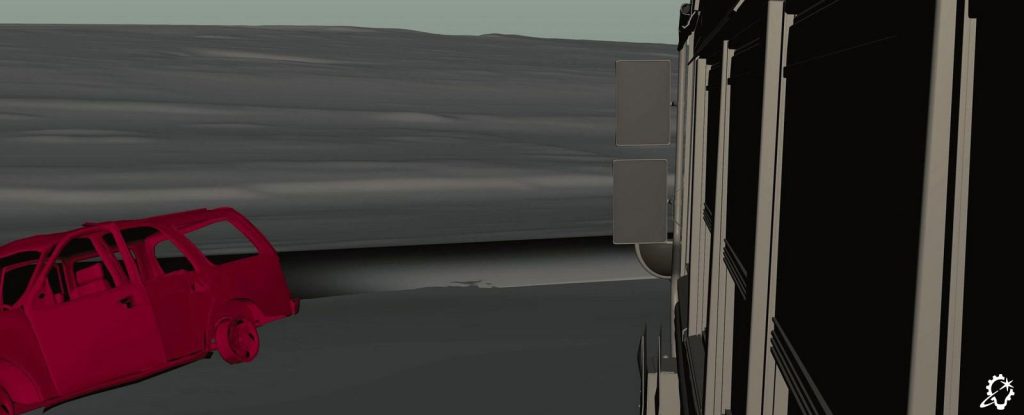

“We built a CG bus, as well as the digital cars we used on the multilane Skyway. We added to the cars they already had to create a sense of everything being jammed together, with people nudging and jostling.” Though a practical bulldozer was captured on location, the ILM team lobbied Paul Greengrass to supplement a fully digital version, which Zaretti notes “looked fantastic. Our team at ILM’s Sydney studio built that for us.”

ILM constructed large environments for the project, such as Roe Road and the Skyway. “We had to build all of that. There were other environments here and there, too. We had to augment Pearson Road’s falling power cables. Paul [Greengrass] did some practically, but we added more to get a chain reaction of the cables coming down and whipping around. We did nine or ten species of trees. We had variants of each species, and for each variant, we had different strength winds going through several levels of fire. We must’ve had hundreds of tree variants in total, as well as bushes and grass. One of the biggest technical challenges was the scale of the event,” Zaretti advises.

“When it came time to design the shots, we already had these component parts and could drop them in. Then, when we needed to do a hero simulation for something in the foreground, we could simulate that,” Zaretti continues. “Our effects team was amazing, and Billy A. Copley was our effects lead. [ILM digital artist] Matthieu Chardonnet devised a really cool fire setup where, once we had a look that we liked, we could essentially paint where we’d want the fire to be on the trees. Within a few hours, we’d have a first pass of how it’d look. Normally, doing that work would’ve required a couple of days turnaround.”

Dynamic Details

Zaretti and the ILM team considered their visual effects work as another tool the director could utilize to tell this immensely important story. “Despite the fact that some of the shots are perhaps 90% visual effects, they were always supporting what had been filmed. We viewed the fire, smoke, and embers as a character,” Zaretti explains, noting that Paul Greengrass felt the ember cam shot was the film’s “Jaws moment.” “The fire is coming for you, and there’s this impending doom. It is the protagonist in the film – it’s the baddie.”

The scene in question finds the camera weaving through the forest from the fire’s perspective, as the smoke and embers close in around the trapped bus. “That was a big operation. The nature of Paul Greengrass’s dynamic camera shots meant that you never focused on anything for too long. Suddenly, you come to this calm, slow, and long piece of track material through the woods. It was entirely digital because the filmmakers wanted to completely art direct where they went. We had an environments build for our forest, which we used for the rest of the show, but we increased the resolution for this particular shot and simulated all of the grass,” Zaretti declares.

Incorporating the original 2018 fire conditions increased the scene’s realism and sparked a somber thought for the ILM artists. “The reason the event was so devastating was because the extreme winds made the fire spread, so we always had to convey a sense of high-directional wind by simulating the grass being blown. The environment looked so good, and we wanted to show it off, but it needed to be dark. We had to bring it down and use the distant firelights to illuminate it. We wanted it to feel realistic, which was enough to make it terrifying. It’s difficult because I kept getting excited about our shots – but then I reminded myself that this actually happened and must have been absolutely horrifying,” Zaretti states.

Unexpected Undertakings

ILM’s contributions to The Lost Bus consist of numerous tasks that casual audiences might not typically associate with visual effects work. When McConaughey’s character exits the bus to survey the fiery landscape surrounding it, ILM trained its efforts on a surprising feature. “The scene needed to be windy, but they didn’t have the wind machine on set at that point,” Zaretti remembers. “So, we rotoscoped the beautiful curls in Matthew’s hair and did a comp shake on those to suggest the wind was stronger than it was.”

For the sequence where the bus embarks on its final escape down a narrow road, Zaretti’s ILM artists assessed key factors relating to the fire’s intensity. “If you have too much fire, you’re just going to have a big sheet of orange. As a viewer, you need to see identifiable objects in there to give it some composition. We took a little creative license to guarantee that the audience would know what they’re seeing. Where’s the bus? Where’s the danger? We also played with the density of the smoke to allow shots to be revealed as you go along,” Zaretti divulges.

Even the digital trees were painstakingly reviewed by Zaretti and his ILM colleagues. “At the end, we started on our ‘tree assassination’ rounds. Usually, the procedural winds we added in turned out spectacularly, but they’d occasionally cause a tree to appear a bit suspect,” Zaretti reports. The ILMers searched for and removed any trees that didn’t pass their quality control test, verifying that every tree that landed on-screen behaved naturally.

Detecting Daylight

The Lost Bus reaches its cathartic crescendo when the bus finally exits the fire, traversing the edge of the smoke cloud, and emerging into the safety of daylight. “That was a neat shot, and very big. It was driven purely by reference because we had footage of people driving through smoke as it goes from black to a slightly lighter shade. Then you get a hint of daylight coming through until suddenly it’s daytime and everything seems normal,” Zaretti remarks.

“That shot was an interesting one to put together, to transition from one environment to another, as we did end up needing to go all digital. The daytime section was the same environment we built previously, but because it’s bright out, we had to confirm all the details, like the tree simulations and so on, were there. We put in the CG bus windshield with the wipers, and we had a simulation for the embers. The bus was splatting into the embers, and due to the speed of the bus, the embers sort of floated to the side and got caught underneath the windscreen wiper. All of these details helped convey the sense of travel.”

Committed to Collaboration

As the ILM visual effects supervisor on The Lost Bus, Zaretti notes that he had the honor of overseeing every ILM shot and deciding whether they were up to the company’s high standards. However, Zaretti reserves the bulk of his praise for his artists, pronouncing, “When all the work is presented in our dailies, I’ll sit in a room and see a shot for 30 seconds, and I’ll already have people from production tapping their watch to say I have to move on and keep the pace up. [laughs] The people who really know the shots and contribute are the artists that are doing them. They’ve sat there for two or three days to make the shot beautiful, and then they present it to me.”

Of his review process, Zaretti affirms, “My artists know their shots better than I do, and I’m just looking at a snapshot in time. I have a gut instinct, and I’ll say what I see, but I enjoy it when other people have opinions because I’m but one person. I cannot see all of the things, all of the time. I value having such an excellent team around me that sometimes helps me spot obvious things that I’ve missed. I’m only human, so I encourage it to be a team effort. This is how we make great work, because we’ve got great people.”

Zaretti is also keen to point out the contributions of CG supervisor Jamie Haydock, a fellow member of the ILM London studio. Haydock, as Zaretti explains, was essential to creating all of ILM’s visual effects shots. “His technical knowhow and level headedness kept everything ticking along so well, and he technically enabled the FX artists to let loose and be creative with some very tricky manipulation of our still fresh USD [Universal Scene Description] pipeline.”

Remarkable Reactions

Eight months after completing his work on The Lost Bus, Zaretti and his wife had a chance to see the finished film at a premiere. “It was one of the most stressful things I’ve ever watched, and my wife felt the same way,” Zaretti reveals. “At no point was I inspecting the visual effects, because you’re just in the story. Paul Greengrass has a documentary style that doesn’t allow you to stop and pause and analyze. It’s not too much or over the top – it’s just storytelling. It’s a perfect example of supporting visual effects doing what needs to be done – and doing it well.

”Speaking of the film as a whole, Zaretti proclaims, “I am immensely proud of The Lost Bus. Firstly, because of the work that we did. Secondly, I do think we’ve respected the event itself and what happened that day. Thirdly, it’s a really good film. Visual effects aside, it’s a nice change to work on something that’s so grounded. When I’m working on a fantasy project, it doesn’t have the degree of gravitas that this one did. This was a terrible event. People lost their lives, and the people who survived will never forget what’s happened. It was important that we did it justice.”

—

Jay Stobie (he/him) is a writer, author, and consultant who has contributed articles to ILM.com, Skysound.com, Star Wars Insider, StarWars.com, Star Trek Explorer, Star Trek Magazine, and StarTrek.com. Jay loves sci-fi, fantasy, and film, and you can learn more about him by visiting JayStobie.com or finding him on Twitter, Instagram, and other social media platforms at @StobiesGalaxy.